The Rise and Fall of the Man Who Created Viktor Orbán's System

As Prime Minister Viktor Orbán expends tremendous resources spreading his newfound message of Christian democracy around Europe, his own political fortunes were for decades linked inextricably to the tenacious vision of a single man: Lajos Simicska.

Together, Viktor Orbán and Lajos Simicska reshaped Hungary’s political landscape and economy, creating what Orbán would later call an ‘illiberal state’. This new system, built on state capture and unbridled corruption, would cement Orban’s legacy in Hungarian politics for decades to come.

This cautionary story of loyalty and betrayal is about Lajos Simicska, the chief architect of this system. The following long read is about the rise and fall of Hungary’s most quintessential oligarch.

The original Hungarian version of this article was published in late 2018.

Translation by András Takács. Edits by bn.

There is a house in Gazdagrét, one of the many suburbs of Budapest, only a few blocks away from the highway leading to Austria. Situated in a not particularly wealthy neighborhood, the house itself is rather nondescript. It was built sometime in the 1970s. Its garden is bordered by a wooden fence, just like other houses on the street. Thuja trees line the driveway. The front windows are covered with curtains to block the view from the road.

Over the past decade, this seemingly ordinary house played an instrumental role in shaping the future of Hungary.

After Viktor Orbán and his party gained constitutional supermajority in 2010 and started the transformation of Hungary, the most important political and business decisions of the country were made between the very walls of this two-story house.

Until 2014, 8 Radóc Street hosted meetings and gatherings for Hungary’s wealthiest and most influential people — billionaires, ministers, secretaries of the state and top-level party officials. On weekdays, the sight of state-owned Audis and Volkswagen vans blocking the narrow street was nothing unusual.

Guests — like János Lázár, former parliamentary group leader of Fidesz, who later became Minister of the Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister, and Antal Rogán, Minister responsible for Government Communication — often had to wait for hours before they could meet the master of the house.

As the once-renowned magazine Figyelő recalled three years ago, two Hungarian billionaires chatting on the balcony were spotted by three ministers waiting in the lobby. Visitors had to deposit their cellphones at the entrance and, for a short period of time, they even had to walk through metal detectors.

8 Radóc Street was never an official governmental office, but it was a place where important decisions were made: which Austrian, German, or Hungarian construction companies would win public procurements; which companies would receive state advertising contracts; even decisions regarding the appointment of individuals to public office.

The house once belonged to Lajos Simicska, the first finance director of Fidesz, formerly the most influential man of Hungary.

For decades, Simicska was the most important and feared financial backroom person, the éminence grise in Hungarian politics. After Fidesz’s 2010 victory, he quickly became the most powerful political and financial player in the country.

Until 2014, Simicska and Orbán managed Hungary together. Side by side, these two men built the foundations of a modern single-party state. Orbán secured the votes and ruled in politics, while Simicska provided the financial and economic backing.

After gaining a constitutional supermajority for a second time in 2014, the relationship between the two strongmen worsened to an unsalvageable level. Orbán decided that he had to put Simicska down. The last three years of Hungarian politics was about their war. This cautionary tale showcases what democracy has become under Fidesz.

After 30 years, the career of Lajos Simicska drew to close. Through his right-hand man, the enigmatic backroom man and chief financial officer of Fidesz sold all of his interests to a new economic hinterland encircling Viktor Orbán.

Subscribe to InsightHungary , our English-language newsletter that is the authoritative source for what’s really happening in Hungary!

Starting in the mid 1990s, Simicska and Orban began constructing a finely-tuned system based on corrupt party funding, using an obscure network of companies designed to funnel public funds into private hands. Simicska was the mastermind behind nefarious coalition pacts, secret deals to form political cartels, and call option treaties between Fidesz and MSZP, the successor of the Hungarian communist era state party. He backed Viktor Orbán when, as the leader of Fidesz, his power inside the party and beyond began to wane.

Simicska’s pivotal role in 2010 landslide victory of Fidesz is undeniable. Between 2010 and 2014, he practically controlled the legislative agenda through bills submitted by single members of parliament. Throughout the years, his construction companies and media outlets generated profit in excess of 35 million Euros.

The unexpected, but inevitable, conflict between Orbán and Simicska evolved in the months after the 2014 elections. Insulted and betrayed, Simicska vowed vengeance against Orbán, and told his friends and henchmen he would take on Orbán. But his three-year campaign failed when Fidesz won its third consecutive national election in 2018.

Once powerful and feared, Simicska has now retired. He sold his business interests and disbanded his troops, but his opus magnum – the culture of using raw power, aggression, and hostile takeovers both in politics and business – will stay in Hungarian public life for years, if not decades to come.

Two Against The World

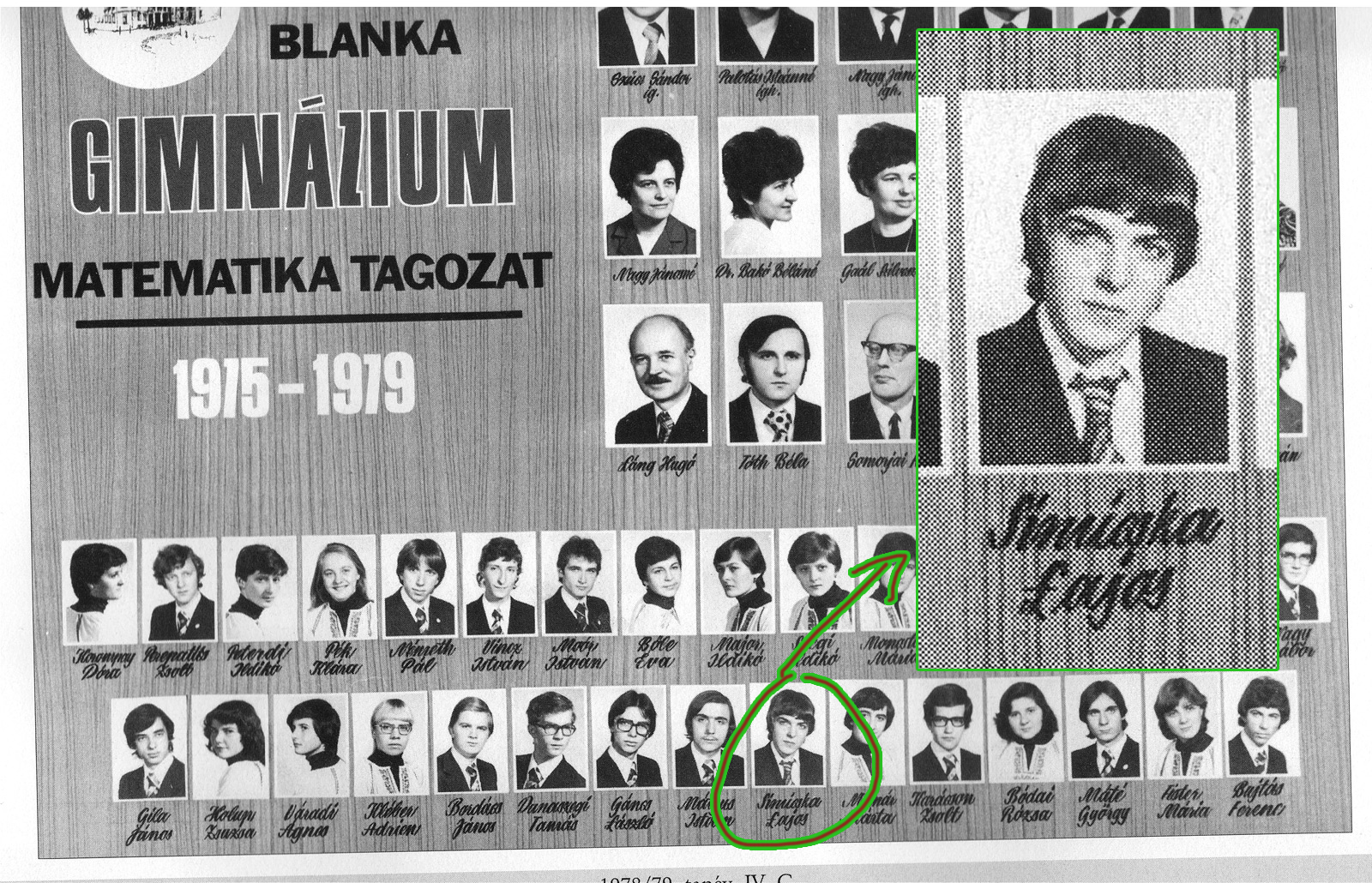

Simicska and Orbán both attended the same high school in the former medieval capital of Székesfehérvár. After serving in the army together, they attended the same special college, the Bibó István College at ELTE Law School, where Fidesz was founded in 1988. Speaker of the House László Kövér and President János Áder were also students at the college, along with many other future Fidesz officials. In an early interview Orbán called Simicska the brightest mind amongst Fidesz members:

‘“ ... the only one was Lajos Simicska. By the way, he was smarter than any of us …”

Lajos, a very capable but rebellious student, was expelled from high school. During his university years, he was reputed for his ability to drink massive amounts of alcohol. The bonds uniting the upper echelons of Fidesz were forged on the football pitch. Despite not playing soccer together, Lajos deeply influenced Orbán’s approach towards politics. Simicska was never popular among Fidesz leadership. His participation in the decision-making process took place through the person of Viktor Orban.

Gabor Fodor, a founder of Fidesz who later joined the liberal party, once described their fraternal relationship as one hardly comprehensible for an outsider. To prove that Simicska has always been a difficult character, Fodor told a story of Lajos walking through a glass door completely drunk, resulting in his body being cut up by shards of glass.

Orbán was raised in Alcsútdoboz, a village of 1,500 inhabitants in rural Hungary. His father, Győző Orbán, was a member of the Communist Party, Viktor was a member of the Young Communist League. Simicska, on the other hand, had a much more difficult family background and was strongly influenced by the anti-communist sentiments of his parents.

Their friendship deepened during their army years, when both were disciplined: Orbán for watching the 1982 World Cup matches, Simicska for making anti-establishment comments. Back then, Simicska’s harsh anti-communist statements left a deep impression on Orbán.

One of the founding members of Fidesz described Simicska as the “smartest thug in the house.”

“He was generally and fundamentally rude, and considered culture a waste of time. On the other hand, he had a certain affinity for strategic planning and mathematics.”

In the early days of Fidesz, the party’s policies were shaped by two groups. Simicska (and like-minded people) thought of the party as an investment to help their ambitions of gaining wealth and power. Others, like János Áder, the current President of Hungary and László Kövér, currently Speaker of the House, had visions of statesmanship, putting the “revolutionaries” of the Austro-Hungarian empire on a pedestal as their role models. And last but not least, in between these two competing factions, stood Viktor Orbán, understanding the importance of both approaches.

Orbán and Simicska recognized they would have to lay the financial foundations of the party in order to catch up with the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP), the post-transition successor of the Hungarian Communist Workers Party, which already had a solid network of real estate, functionaries and connections.The following years would prove to be vital for Fidesz. After the first free elections of the third Hungarian Republic, Fidesz secured 9 percent of vote and entered parliament, but became only the second-largest liberal force after SZDSZ, the Alliance of Free Democrats. Understanding the oversupply of left-wing parties, Orbán and Simicska decided to swing Fidesz to the middle.

Simicska initially worked for Fidesz as a legal advisor. He was relatively unknown to the general public when Orban later asked him to become Fidesz’s director of finance. In complete secrecy, Simicska negotiated a secret deal with the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF), the governing conservative party. As part of this deal, a bill was introduced to provide newly-formed parties with real estate they could later sell. They justified the bill on grounds that the Hungarian Socialist Party had a “competitive advantage” over the newer parties.

The main beneficiaries of this bill were MDF and Fidesz. Both received half a building to serve as their headquarters. They later sold their newly-acquired real estate for the equivalent of 3 million Euros. Cash in hand, Mr Simicska now had the resources to build a network of companies that would lay the groundwork for Fidesz’s business empire.

Hungarian leftists still refer to the bill as the peccatum originale of Fidesz, as the party had to make a deal with the right-wing governing MDF to get their ‘first million’ in a shady way.

In a 1994 portrait written by his former mentor László Kéri, Orbán shared his views of the headquarters-deal:

“My opinion in the debate about selling the headquarters building was always clear. The party has to be independent financially (...) We can only rely on those things we take for ourselves, contrary to our competition who already made a fortune in the past forty years”

Orbán and Simicska always had a ‘two against the world’ attitude. As one former Fidesz founders recalled, Simicska only appeared at party or other events alongside Orbán — he avoided public attention. How the headquarters deal has been handled amplified this notion.

In the early 90s, they did everything in their power to financially consolidate Fidesz and build a party infrastructure. While this plundering attitude alienated leftist and liberal voters, it made it clear that Orbán and Simicska were the only people who understood modern politics in Hungary. After the real estate scandal, the two men worked on establishing their own media empire.

In 1994, Simicska took control of Mahir, a valuable state-owned advertising company, in a public procurement. He also gained control of Hírlapkiadó, one of the largest Hungarian publishing companies, which owned the publishing rights of a major Hungarian newspaper. Simicska formed an alliance with Gábor Liszkay, then CEO of Hírlapkiadó to obtain the company’s publishing rights for 5 years.

Simicska’s dealings nearly destroyed Fidesz. Despite its initial popularity after Hungary’s democratic transition, the party’s popularity dropped to a historic low. Fidesz only secured 7% of the votes in the ‘94 elections, just above the threshold to enter parliament, prompting some founders to quit the party. Gábor Fodor left to continue liberal politics at SZDSZ, as did István Hegedűs and Zsuzsa Szelényi. Zsolt Bayer, one of Orbán’s primary comrades also quit Fidesz. In an interview for Népszabadság in October 1994 he justified his decision with the following:

"We started seeing more and more armed security guards around Dr. Simicska. We started to look like we were hanging out at the hacienda of some Colombian cocaine dealer. There were also more secrets. As the number of secrets increased, so too did the number of important-look people, guys that we couldn’t chat with about women, food, or drinks."

By 1994, it seemed the Fidesz project was over. But Orbán trusted the plans of his financial director. To Orban, Simicska’s strategic planning was more important than ever. Simicska, who, through teaming up with the Hungarian Democratic Forum made a fortune for the party by selling the party headquarters, explained his view of true political power in an interview in 1994:

"The benefits shouldn’t be looked for in which people earn a few million Forints with jobs here and there. The nature of political power is completely different. Our biggest yield comes from our network, which had been developed over the course of many years; a network that delivers yields far more valuable than money. It is a huge mistake to sacrifice this network in hopes of achieving short-term gains. Politics is not merchandise."

Simicska, not popular among core members of Fidesz, always sought allies. He invited Szilárd Kövér, brother of Fidesz strongman László Kövér, to serve on board of the Mahir. Despite making a lot of adversaries with his shady business dealings, with this move, Simicska turned László Kövér, one of Orban’s most important confidants, to his side.

As Hungarian magazine Élet és Irodalom found 5 years later, the equivalent of roughly 3 million euros were funneled from the headquarters deal into a mining company formerly controlled by Orbán’s father. With chief ideologist László Kövér involved in the deal, nobody dared criticize it. Simicska was protected by high-level Fidesz officials. By 1994, Orbán and Simicska seized control of the party’s finances and completely consolidated their power.

May God have mercy on your souls because Simicska won’t

From 1994, Orbán was occupied with carrying out the party’s conservative transformation. The major liberal party SZDSZ formed coalition with MSZP, the governing party. To reposition itself, Fidesz focused on taking over the political right after the decline of the Hungarian Democratic Forum. While Orbán toured the country, sharing his new ideas, Simicska set about building up the party’s finances and media.

Between 1995 and 1997, Simicska and his colleagues sold 16 companies to non-existing persons. With the help of these phantom companies, they evaded the equivalent of 1 million euros in taxes, making funds available for founding of Fidesz’s first daily newspaper, Napi Magyarország.

Thanks to Orbán’s dedication and hard work, Fidesz won the 1998 general elections with the Independent Smallholders, Agrarian Works and Civic Party.

Simicska worked on broadening the party’s channels for publicity. A confidant was appointed director of Postabank, a state-owned bank, which immediately purchased the publishing rights of the Magyar Nemzet, the biggest daily newspaper. They paid the equivalent of 3 thousand Euros to finalize the deal. Using money from the party’s private trust, they also founded a new magazine, Heti Válasz.

Two Simicska confidants were tapped to run Magyar Nemzet: college friend and lawyer Tibor Győri and Gábor Liszkay. Their top 10 clients were all state-owned companies, with state-owned gambling company Szerencsejáték Zrt. and the Prime Minister’s Cabinet Office being billed more than 1 million euros for advertising.

Since the early ‘1990s, urban intellectuals and the financial elite were increasingly put off by the direction of Fidesz, which prompted Orbán to raise a new elite. He asked Simicska to lead the Hungarian Tax Authority, where Simicska’s main task was to help businessmen loyal to Fidesz and to make the life of Fidesz’s opponents harder.

This plan failed. They underestimated the outrage of opposition parties and media. What’s more, Simicska turned out to be completely unsuitable for public service. Journalists blamed him for cooking the tax authority’s books. A scandal emerged regarding the mines owned by Orban’s father and Simicska proved he couldn’t control his temper.

His final outburst was quite extraordinary. On August 29, 1999, he sent a public message to liberal MP Mátyás Eörsi who had publicly questioned his competence. He picked up the phone, dialed the editorial room of his own newspaper, Napi Magyarország, and dictated a statement which ended with the following sentence:

"In the last three months, you killed my father and my father-in-law. May God have mercy on your souls."

Despite these scandals, Fidesz was on track to win the 2002 elections. But a turn of events led to a surprising defeat. Simicska left public life and returned to managing the Fidesz’s business empire.

Keeping Orbán alive

The general elections of 2002 was a close race and yielded the highest turnout in the history of modern Hungarian democracy. The polarization of the political spectrum became irreparable. The anti-communist bloc, led by Fidesz, faced off against the post-communist MSZP and their liberal allies.

Fidesz encouraged voters to keep wearing the symbolic cockade of the March 15th revolution until the elections to show that true patriots vote for Fidesz. Orbán’s message, that “the nation cannot be in opposition,” also started to spread during these months.

The Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) eventually won 42% of the votes, while Fidesz only won 41. The Socialists formed coalition with the liberals, and the right-wing parties went into opposition. Fidesz supporters united like never before. The majority of them felt betrayed by their fellow citizens, and Orbán refused to accept the election results.

A small group of people even formed a blockade on the Elizabeth bridge for a few hours, demanding a recount. Orban went on to form a movement called Civic Circles to keep Fidesz voters engaged.

Surprisingly enough, Fidesz’s base united like never before after the election defeat. Orbán couldn’t have kept them motivated without the help of Simicska and his media empire.

After the elections, Orbán promoted Heti Válasz, Simicska’s magazine, to his supporters. On June 18, 2002, Magyar Nemzet disclosed a top secret document with proof that the socialist PM Péter Medgyessy worked for the Communist Secret Service in the 1980s. At first, the story appeared to be leaked by a legitimate whistleblower, but it was later confirmed that the dossier came directly from the Fidesz headquarters.

Simicska founded HírTV, the first news-only television of Hungary, in December, 2002. At the time, rumor held that the television station was funded by micro-donations from the Civic Circles. The truth, however, was that the first few million Euros of fuding came from Mahir, Simicska’s company. HírTV and Magyar Nemzet became closely intertwined under the management of Gábor Liszkay, who diligently pushed Fidesz’s political messaging to their audience, thus projecting power and unity.

Advertising money from state-owned companies stopped flowing after the electoral defeat. Simicska then founded Lánchíd Rádió, a radio station. Keeping the media empire up and running demanded a huge financial effort, but Simicska was optimistic. He saw it as a long-term investment that would eventually pay off when Orban returned to power.

One former liberal MP summarized this strategic approach in 2010 as a signature trait of. Simicska:

“While the socialists stole money and took it home one by one, Simicska and his men funneled it into their empire for further use.”

Media was an important instrument to consolidate Orbán’s power within the party. When Fidesz lost to MSZP for the second time in 2006, rumors started to spread that János Áder aspired to become the leader of the party. A few weeks after the elections, the editors of Magyar Nemzet attacked Zoltán Pokorni, then VP of Fidesz, in an open letter. They accused him of being too “jew-friendly,” and of organizing a coup within the party to oust Orbán.

A few months later, another anonymous author from Magyar Nemzet outed historian Mrs. Mária Schmidt, and businessmen Zoltán Spéder and Kristóf Nobilis.

Rumor held the three conspired to start a new right-wing party. The three influential right-wing individuals were cast as traitors by the Orbán-friendly media. Former Magyar Nemzet editor Tibor Pethő later wrote in his book that the articles written against these people came on the command of Orban’s inner circle. After two electoral defeats, Orbán desperately needed the protection of Simicska’s media.

In 2006, an unexpected gift fell into Orbán’s lap: the infamous “Speech of Őszöd”.

In September 2006, Hungarian public radio aired parts of a recording from the Hungarian Socialist Party’s annual conference, where the key speaker was then Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány. In the company of his fellow party members, Gyurcsány talked about how the party lied to the people throughout the campaign in order to win the elections, how they faked the annual budget, and that the government was in serious debt. The leak prompted riots in Budapest. The outrage inspired people to back the strongest opposition leader: Orbán.

By constantly reporting on the riots, Simicska's HírTV and Magyar Nemzet played a key role in helping Orbán secure his power inside Fidesz.

Years later, news director Péter Tarr revealed some details to a media magazine about the daily workflow of HírTV under Fidesz rule: “People responsible for government communication came to the office on a weekly basis. They had meetings with executives, where they decided who would be invited to which shows, and which topic would be reported and how.”

Directors of these companies were people loyal to Orbán. The media empire was held together by Gábor Liszkay, Simicska’s right-hand man. The editor-in-chief of Heti Válasz was Gábor Borókai, Orbán’s former spokesman. While they couldn’t force the government to hold early elections, they were able to keep the revolutionary narrative alive for years. Fidesz’s base continued to unify.

In 2008, the Socialist-Liberal government sought to introduce social reforms aimed at introducing in-person contributions toward healthcare and higher education. Fidesz immediately set into motion a referendum challenging the plans. The campaign was immensely successful, earning Fidesz a 90-10% vote for eliminating the reforms. It became clear at that point that Fidesz would win the 2010 elections, and Simicska started planning his economic takeover.

The takeover had been in the works well before the 2010 elections. Even by 2008, it was a known fact that Simicska and companies close to the Socialist government had a fruitful relationship. The cyclical nature of governance was in both parties’ best interest. While politicians on both sides publicly called each other traitors, their respective business hinterlands got on grandly.

Simicska’s main counterpart in the Socialist party was regional president and financial director László Puch. The two were introduced by Orbán, who knew Puch from the times when they played together on parliament’s football team.

After Fidesz’s attempt to subvert Hungary’s right-wing parties in the 1990s, Hungarian Democratic Forum built a campaign on speculations that Fidesz and MSZP made a deal to divide public procurements 70-30% in favor of whichever party was in government. A few years later, Minister of the Prime Minister’s Office János Lázár openly mentioned the Puch-Simicska pact as a matter of fact in the National Assembly.

In a 2007 interview with Index.hu, Puch openly talked about ‘messages sent and received’ between himself and Simicska. According to Puch, this relationship wasn’t political. But Orban and his men had a very different idea about this pact after the 2010 election. Fidesz only respected the agreement when it was in opposition.

In 2009, the two major parties cooperated in getting their hands on the country’s largest radio frequencies. In Hungary, the owners of the frequencies are selected by the nominally independent Media Council. But Fidesz and MSZP could easily manipulate the Council’s decision, and the two radio stations with the biggest audiences were assigned to their respective businessmen. Class FM went to Simicska, and Neo FM to Puch. After winning the 2010 elections, Fidesz revoked all the advertising spending funneled to Neo FM and discouraged private companies from advertising there. Neo went bankrupt.

Another important sector where Fidesz and MSZP cooperated was in construction. Simicska’s construction company, Közgép, was very successful with public procurements even before the election victory. Közgép participated in renovating a rail line connecting Székesfehérvár – the hometown of Simicska and Orbán – with Budapest.

One of the signature projects of the era was the renovation of the Margaret Bridge connecting Buda and Pest. Collusion between Fidesz and MSZP companies increased the price of the project from the initial 20 million Euros to well above 100 million.

The Socialists hoped Fidesz would return the favors after coming to power, but MSZP collapsed after its crushing defeat in the 2010 elections. With a constitutional supermajority, Simicska had no intention of honoring past deals.

The Untouchables

By the time Viktor Orbán won the elections for Fidesz in 2010, Simicska hadn’t given an interview to the press for six years. He was practically invisible to the public. Ten years had passed without any photos of him surfacing. After 2010, Közgép started to win an increasing number of public procurements. After 2011, if a construction consortium didn’t include Közgép, it had no chance of winning state construction contracts.

Orbán gave complete authority to Simicska in deciding finance and energy policies. Orban needed a solid financial background to challenge Sándor Csányi, owner of the largest Hungarian bank and wealthiest man in the country, and multinational companies.

During the spring of 2010, Simicska spent weeks in Felcsút, Orbán’s home village, discussing with Orban who would take which key positions in the new government. Zsolt Nyerges, a newly-appointed director of Class FM and Közgép, became the liaison between Orbán and Simicska. Nyerges was responsible for selecting the new heads of institutions which oversaw public procurements.

Róbert Gajdos, a close friend to Nyerges, became the head of the Procurement Council,

Zoltán Petykó, a former board member at Simicska's Közgép, became the director of the Development Agency,

Orbán and Simicska's former lecturer Tamás Fellegi headed the Ministry of Development, and

Zoltán Schváb, a former board member at Közgép, became the state secretary responsible for transportation at the Ministry of Development.

The two men carefully carved up sectors where they would make fabulous wealth without any need to innovate, relying exclusively on overpricing and manipulating laws.

Simicska’s henchmen took control of key positions in public media as well. They were the buyers and sellers. The Media Authority gave all non-Budapest frequencies to Simicska’s Lánchíd Radio. Trusted men were appointed directors of the most important state advertisers. Kálmán Szentpétery became the head of Szerencsejáték Zrt. Csaba Baji became the chief executive of MVM, the Hungarian electric company. These strategic appointments ensured advertising funds would flow in the right direction.

It didn’t take long before players on the construction market realized they would have to team up with Közgép and its subsidiaries if they wanted a piece of the public procurement pie. The system started to operate immediately after the Fidesz’s electoral victory. As leader of consortium, Közgép won over a billion euros worth of procurements in a year and half.

Simicska was feared in Hungarian public life. Feared by journalists and politicians alike, his name was only whispered in parliament. Behind the scenes, Fidesz parliamentary group leader János Lázár, Minister for Rural Development Sándor Fazekas, and Minister for Development Tamás Fellegi were all frequent guests in the Radóc Street office. They often had to wait for hours in the lobby before they could see “The Lajos.”

Between 2010 and 2014, the government introduced special sector taxes to build dependencies between the state and the largest companies operating in Hungary. Between 2010 and 2012, business leaders were forwarded to Simicska to make their deals.

Avoiding the public, Simicska’s ruthless business practices were comparable to those seen in gangster films. The perception of his power was almost mythical. He was also feared inside the party.

As one former executive of a large corporation described, the meetings in Radóc Street were “ice-cold discussions.” Guests were instructed to leave their phones at the reception desk. Metal detectors were installed in the building. A minister, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said he once justified his early departure from a cabinet meeting with having an appointment in Radóc Street.

This system was built around the vision Simicska discussed in his 1994 interview with Népszabadság — a network of cadres at the foundation, dependencies built with years of work which are more valuable than money in the long-run.

To illustrate the captured state, consider the case of ESMA, a Spanish advertising company that owned street billboard spots in Budapest. A competitor of Mahir, Simicska’s advertising company, it wasn’t long before they were approached to sell their business. Weeks after refusing the offer, Fidesz introduced a bill forbidding the to company place ads on street poles.

They used similar mafia methods to seize control of Metropol, a free daily newspaper handed to passengers at metro stations and traffic hotspots around Budapest. When Metropol’s owners, Swedish media investor Metro International, refused to sell the company, Budapest’s Transportation Authority threatened to introduce new regulations imposing restrictions to the use of public transportation areas. A trusted man, Károly Fonyó, took over Metropol. Soon, the newspaper was flush with public advertisements.

In less than two years, Simicska built a spectacular system to funnel state funds into loyal hands. Total state capture was almost complete.

In the summer of 2012, I (then as journalist at Magyar Narancs political weekly) was tipped off about a restaurant near Lake Balaton. Simicska was a frequent guest of the restaurant and often sat out on its terrace.

After weeks of waiting, Magyar Narancs photographer Dániel Németh finally managed to snap a photograph of Simicska, who hadn’t been photographed for 13 years, sitting together with his media manager Károly Fonyó.

The meeting was obscure. Instead of speaking to each other, the two moved small cards (probably with company names on them) around the table, sometimes stacking them on top of each other.

Virtually all deals made by Simicska were politically-motivated. Right before the 2014 election, Orbán and Simicska used options contracts to tie the fate of the countries largest media companies to themselves, effectively ensuring their hidden influence for years to come:

The two men scared potential buyers away from TV2, Hungary’s second largest commercial television broadcaster, by introducing special advertising taxes and signing options to buy the company.

They trapped the owner of Index.hu, Hungary’s most widely read news site, through his interests in the Hungarian Post and Savings Bank, later signing options for Index.hu as well.

They forced German and Swiss media companies Axel Springer and Ringier to sell them the publishers of Népszabadság, Hungary’s most renowned leftist daily, and Nemzeti Sport, a sports daily, to a front. This was done by jeopardizing the fusion of the companies with the help of Hungary’s competition authority.

While Orbán and Simicska laid the foundation of their empire for their next term in government, they didn’t forget to pocket public funds on an unprecedented scale. According to public databases, Simicska took home well over HUF 60 billion (USD 210 million) in profits in six years.

End of an era

While the exact reason for the Orbán–Simicska breakup is unknown, tension between the two men was tangible. Orbán wanted more control in governance and business, but Simicska and his circles were so deeply embedded into the state structure that getting rid of them required enormous effort.

By early 2014, an increasing number of mayors in the countryside started complaining to Speaker of the National Assembly László Kövér that they were unable to employ local entrepreneurs because Simicska’s Közgép was winning every public procurement.

Árpád Habony, a personal advisor to Orbán, and then richest man in Hungary Sándor Csányi were engaged in constant battles with Simicska. These disputes came up frequently during Orbán’s monthly dinners with President Áder.

Without involving Simicska, Orbán and Csányi had begun negotiating a natural gas deal to be run through MET, a gas trading company, a venture that earned annual profits in excess of EUR 30 million per year.

There was a conflict between Simicska and Lőrinc Mészáros, an old friend believed to be a front for Orbán, concerning the construction of a stadium next to Orbán’s house in Felcsút. Simicska’s deputy refused to perform work until the client, the Puskás Foundation, which was headed by Mészáros, paid for the work in advance.

By Simicska’s own account, he last met with Orbán in April 2014, after the elections, when Orbán told him of his future plans. According to Simicska, Orbán wanted to allow Russia to gain more influence in Hungary and wanted to see the rise of new Fidesz-backed media moguls.

In subsequent interviews, Simicska repeatedly cited Orbán’s Russia-friendly position as the causus belli between the two men. Simicska claimed Orbán asked him to buy RTL Klub. When Simicska protested against the idea, Orbán said: “Doesn’t matter. Rosatom will buy it for me.”

Illustrative of just how captured the state had become, the government became dormant by the summer of 2014. Government ministries and agencies lacked the courage to appoint people to important positions.

In September 2014, Simicska unexpectedly invited journalists and photographers to the inauguration of an equestrian track where he appeared with most of his loyal people. Later, he even mentioned running for parliament in his town’s by-election. Orbán tried to consolidate the relationship and make peace during this period. He failed, despite enlisting the help of Minister of the Chancellery János Lázár.

On the February 5, 2015, the government suddenly modified the advertisement tax, introducing a new 5-percent tax rate. As a result, Simicska promised all-out media war in an interview with leftist newspaper Népszava.

The next day, an unexpected turn of events triggered what would come to be known as the infamous “G-Day.”

Management of Magyar Nemzet, Simicska’s flagship newspaper, which was led by Gábor Liszkay, suddenly resigned.

Simicska picked up his phone and started giving interviews. He gave more interviews in that one day than in the past ten years combined. When independent news site Hír24 called, Simicska referred to his former managers and Orbán as “geci,” which translates to “semen” and is one of the most insulting and vulgar terms in the Hungarian language.

Simicska knew of Liszkay’s departure, but he was caught off guard by news that others had also quit. He interpreted the resignations as betrayal, a coup provoked by Orbán.

Simicska was so upset that when I (then as a journalist for Magyar Narancs) asked him how much he paid for Liszkay’s share, he couldn’t answer at first:

“HOW THE HELL WOULD I KNOW! OKAY, WAIT, I’LL HAVE TO ASK. (...) SOMEWHERE AROUND 0.3 MILLION EUROS”

Simicska repeatedly claimed he was betrayed, but vowed to fight back. The Geci-scandal started.

Weapons turned against their master

After splitting with Orbán, Simicska often spoke about vengeance to his friends and family. The substance of these discussions often made it to the news. He even became fairly self-critical:

“AFTER UNLEASHING THE ORBÁN-PHENOMENON, IT’S HIS DUTY TO GET RID OF IT”

But Simicska came across as desperate. His claim that the conflict with Orbán was rooted in the prime minister’s Russia-friendly views didn’t seem too credible. Investigative journalists at Direkt36 found evidence that Simicska negotiated business and policy in Russia well before the 2010 Hungarian elections.

After 2015, Simicska worked tirelessly to see a change in government. He started publicly backing the former far-right party Jobbik. He kept himself hidden from the public eye, but the vast network of people loyal to him ensured he still had a lot of influence in Hungarian politics.

In the autumn of 2015, when Andy Vajna, a movie producer and friend of Orbán, announced he would buy TV2, Simicska showed his hand, disclosing an option contract for the television channel. He had no intention of buying TV2 (it’s operating costs were enormous), but the disclosure showed Fidesz and the general public what weapons Simicska had at his disposal.

During the campaign for the 2018 national elections, Simicska exercised his option to buy Index.hu, Hungary’s largest news website, saving it from Fidesz who had their sights set on the outlet. Simicska made it known that he wanted to exact revenge and govern.

Subscribe to InsightHungary , our English-language newsletter that is the authoritative source for what’s really happening in Hungary!

“Once they lose power, they will be called to account for their actions. The hour of justice will come and they will all rot in prison,” Simicska told Index in 2015.

In the meantime, Simicska’s media group underwent went a significant transformation. HírTV signed famous liberal journalists like Alinda Veiszer and Olga Kálmán. Jobbik politicians started to appear in the studio as guests.

Granting editorial freedom became Simicska’s primary interest. A handful of workers quit and transitioned over to Orbán-affiliated outlets during this time. The staff of Fidesz-friendly investigative journalist show Célpont even recorded a short video of them saying “We don’t think Orbán is a semen”.

In the meantime, all of Simicska’s companies became unprofitable. Between 2016 and 2018, HírTV, Magyar Nemzet, and Lánchíd Rádió generated over 14 million Euros of losses. In just two years, Közgép’s revenue fell from around 370 million Euros to 17 million. The only companies which remained profitable were his advertisement firms.

In 2015, Simicska gave several interviews in which he seemed disoriented. In an interview to the leftist magazine Magyar Narancs, he suggested he was in the possession of confidential information about Orbán being a snitch for secret police in the communist era. Later, in a hysterical fit, he sprayed graffiti on walls in and around Veszprém. Despite the hollow appearance of his actions, the prime minister and his inner circle considered Simicska and Jobbik the only genuine threat to Fidesz.

Despite Simicska’s shallow public attacks on the prime minister, his powerful reputation led many to believe he still had aces up his sleeve before the election.

The government responded by attacking Simicska’s relationship with Jobbik, prioritizing the issue for voters. The journalists now attacking Simicska were once his employees.

As time passed, Simicska began to divest from his businesses. Ironically, Fidesz-affiliated businessmen now used the same methods Simicska once devised to wreck the former party financier’s empire.

State advertising fell under the purview of the Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister, led by Antal Rogán. This prevented state-owned companies from accidentally buying ads in Simicska’s media outlets.

1,440 acres of land were taken back from Simicska, and the government later raised the price of long-term land leases.

The State Audit Office opened an investigation into Közgép, which was shortly banned from taking part in public procurements. Courts later found the ban to be unlawful. The construction of a new highway was shut down and payments to Közgép were suspended.

The Mayor’s Office of Budapest terminated the agreement with Mahir, resulting in the company’s revenue stream being blocked.

Metropol was forced out of transportation hubs after Árpád Habony and his partners used political leverage to persuade the Budapest Transport Company to terminate the company’s contract.

The National Media Authority suddenly dished out several penalties to Class FM, Simicska’s radio station. The station was later denied an extension to its radio frequency.

In 2017, the National Tax Authority started investigating Simicska’s poster companies on suspicion of budgetary fraud.

The Fidesz-dominated National Assembly enacted an unconstitutional bill to suffocate Jobbik’s campaign. The President of Hungary signed it without even sending it to constitutional review.

Tables were turned on Simicska. The government weaponized state institutions to eradicate him. Despite this, he kept fighting against Fidesz until the end of the 2018 campaign.By the end of 2017, Magyar Nemzet started to print increasingly scandalous stories about the prime minister and the ruling party.

They revealed the luxurious hunting trips of the Deputy Prime Minister Zsolt Semjén in Sweden, where he illegally killed at least one semi-domesticated reindeer and carried the animal away with a helicopter.

Magyar Nemzet also printed information about a secretary of state with an offshore bank account in Belize with more than 3 million Euros on it. In the final weeks of the campaign, Orbán and his closest colleagues seriously considered the possibility of Simicska disclosing something so outrageous that it could change the outcome of the elections.

A particularly grotesque phenomena in the final stretch of the campaign was the faith that opposition voters placed in Simicska.

Given the shortage of credible alternatives, even the liberal intellectuals saw him as the only savior of the country capable of destroying Fidesz and the Orbán regime. This bizarre situation perfectly illustrated the condition of Hungarian domestic politics:

THE OPPOSITION RELIED ON THE ONE PERSON WHO DID THE MOST TO ENSURE ORBÁN’S ABSOLUTE POWER OVER HUNGARY, A MAN WHO ALMOST SINGLE-HANDEDLY TRANSFORMED HUNGARIAN POLITICS INTO THE ART OF MAKING PUBLIC FUNDS PRIVATE.There were rumors that Orbán made Simicska an offer he couldn’t refuse after the unexpected defeat of Fidesz’s candidate in Hódmezővásárhely’s mayoral by-election in early 2018. Some suggested Orbán exploited Simicska’s paranoia, who often talked about the possibility of being killed.

As investigative journalism center Direkt36 reported, Simicska claimed to take out the proverbial insurance policy, recording a video in which he shared secret information about Orbán. In early 2018, Simicska acquired a radiation detector after receiving a threat that someone might try to eliminate him with radioactive substances.

In the end, Simicska disclosed no explosive details capable of derailing Fidesz’s campaign. Orbán’s ruling party won the election with a third consecutive constitutional supermajority. One day after election, Simicska started to dismantle his media empire. Two days after the election, Magyar Nemzet and Lánchíd Rádió ceased to exist. Cutbacks were made at HírTV. A few weeks later, the publisher of Heti Válasz went bankrupt. Lőrinc Mészáros, the symbolic front for Orbán, took control of Simicska’s favorite handball team.

By the summer of 2018, Simicska finally laid down his arms. Zsolt Nyerges announced he had taken over Simicska’s businesses, and rumors began to spread that some 60 companies once owned by Simicska would end up with Mészáros. These companies gravited to Mészáros by September, starting with HírTV. Mezort, a company that held Simicska’s lands, soon followed. Közgép was also bought by Mészáros.

“Traitors” were expelled from HírTV by Gábor Liszkay, Simicska’s former media chief. Liszkay then steered the channel back into service of Fidesz.

Last autumn, Népszava reported that Simicska sent his son to the US, and that the whole family would follow. There has been no confirmation so far that Simicska has left the country. As Direkt36 reported, Simicska now spends most of his time at his manor in the village of Hárskút. He avoids the press.

His health has declined dramatically over the past two years. Left with his family’s goat farm business, he has been reduced to obscurity, but the lasting effect of his achievements will not fade for a long time.

The Hungarian government will continue to operate as it did before 2015. The only difference is that Fidesz MPs and key decision-makers won’t go to Radóc Street for instructions. Instead, they will venture to the Office of the Prime Minister, or Orbán’s countryside manor in Hatvanpuszta.Decisions concerning public procurements are no longer made by the Ministry of Development or the Development Agency. These decisions are now made by the Office of the Prime Minister.

Those who sided with Simicska must now do penance.

Details concerning shady residency bonds scandals, funneling corporate taxes to sports clubs, overpriced public procurements, and stadium construction details are now finalized on the prime minister’s desk. The architect of the system is gone, but his system continues to operate.

(In the lead photograph to this piece, the picture shows Lajos Simicska and confidant Károly Fonyó sitting on the terrace of Kikötő restaurant near Lake Balaton in 2012. The photo was taken by Dániel Németh of Magyar Narancs)