The Art of Media War - This is how Viktor Orbán captured the free press in Hungary

Since the 1990 disintegration of the Eastern bloc, all democratic governments of Hungary have made attempts to reconstruct the media sector according to their political interest. Yet, none had acquired as much capacity, power and ambition as Viktor Orbán’s coalition, which was elected with a two-thirds supermajority in 2010.

Orbán saw the media as a battlefield; occupied by enemy troops and crowded with territories for potential expansion. This was in part due to his defeat by the socialist as an incumbent in 2002. He aimed to crush any emerging opposition, and took office with the goal capturing the whole sector, thus winning the media war.

At first, one of his long-lasting confidants, the ruling party’s founder, Lajos Simicska, was appointed as his admiral for the fight. Times changed, the two fell out and the alliance of this duo ended in 2014, completely reshaping the status quo. Eventually Orbán had to see out his strategy against his once trusted media oligarch, broadcasted by the remnants of the free Hungarian media.

The conflict is unlikely to come to an end in 2022. It's in the nature of the regime to continue the battle, perpetual conflict is at its core.

There are still some players standing, and only one can win the war. The media industry has gone through some considerable changes in the past 12 years. Therefore, it is worth analysing which steps of Viktor Orbán lead to the near complete capture of the Hungarian media.

In 2010, one of the very first international conflicts of Orbán’s government revolved around the newly enacted media law. The regulations caused a public outcry, because they enabled the establishment of a joint institution overseeing of the press, the national news agency, and the Hungarian media market, the National Media and Infocommunications Authority and the Media Council.

The top leadership of this new institution were appointed by the government, gaining an unprecedented 9-year mandate that did not align with European standards. Annamária Szalai, a former member of the ruling Fidesz party was chosen as the first president. Szalai passed away before her mandate was up and following her, Mónika Karas took the office, a media lawyer, who had been working for Fidesz since the early 90s.

The new media concept was already set by 2009, awaiting execution. Orbán did not only aim for censorship, he rather wanted to capture the mediasphere. He knew that controlling the body which oversees this sector was necessary for his political ambitions.

A fierce public debate, and worried questions from the EU have followed the announcement of the new legal framework. Looking back now, it's clear that some of the more outrageous clauses, like the ability to issue excessive fines for newsrooms, were only there for bait: the government agreed to change the unsettling details, but stuck to the passages that - in the long run - proved to be pivotal for media capture.

From this point on, all media matters were politicized; the government decided on streaming rights, on the allocation of regional broadcast radio frequencies, state financed advertisements, or the regulations on commercial television channels.

Just under 2 years, the new mechanisms ensured that Lajos Simicska could gain access to some of the most prominent channels: Class FM, Lánchíd Rádió and TV2. While the Simicska-related Nemzeti-group expanded, the media authority prevented unwanted mergers. The German Axel Springer and the Swiss Ringier were not allowed to join forces, until they were willing to sell some of their key assets to government aligned buyers.

The buyer was Heinrich Pecina, an Austrian businessman thought to be a frontman for government interest. He acquired several regional papers, the daily National Sport and Népszabadság, considered the paper of the record in Hungary. Pecina consolidated his media portfolio starting the publishing house Mediaworks, which was later acquired by Lőrinc Mészáros, (currently the wealthiest man in Hungary) and close ally of PM Orbán. Hence the media council laid the foundation for the near complete monopolisation of the Hungarian media sector.

National media, in service of the ruling party

Orbán has never believed in the concept of 'public service’ media.

His political creed is based on perpetual conflict, and therefore is incompatible with the concept of independent national institutions. His pursuit of a partisan media structure started in 2002. Following his defeat to the socialists, Orbán initiated a referendum with the aim of establishing parallel state television and radio channels half of which would always be under the authority of the opposition. From this point forward, it became clear that a potential Fidesz victory would bring about fundamental changes, transforming the public service media for the sole service of the party.

The new media legislation abolished the advisory boards of the Hungarian News Agency (MTI), the Hungarian Radio and Television Group. Supervision of the public media services was brought under the authority of the Media Services and Support Trust Fund. Fidesz seized control through establishing a framework, where the delegates of the ruling party and the Media Council became representatives of the all-time government majority on media affairs.

Media financing was restructured and public service asset management was reassigned to MTVA—the umbrella organisation for public service media. The national news agency’s most important offering, its wire service became free, undercutting all competitive private platforms on the market. Allocated governmental budget was more than doubled for the MTVA, and most of their contracted suppliers came from the circle of Fidesz-related media entrepreneurs.

From 2011, deceit became an everyday practice on public media platforms. In April of that year, Daniel Papp, a new associate editor of the public television, distorted a report about Daniel Cohn-Bendit an MEP critical of the Hungarian government. A couple months later, the national television broadcasted a retouched interview, in which they blurred out Zoltán Lomnici, the former president of the Supreme Court. They also rooted out any opposition from within: the companies of MTVA fired more than a thousand employees in under a year.

The restructured news channels played a key role in Orbán’s hate-fuelled anti-immigration campaign during the 2015 refugee crisis. By this point it wasn’t only opposition politicians and other other public figures that got „banned” from the tv screens, expressions such as ‘refugee’ were completely censored from the public media.

Crews were clearly expected to deliver scenes from the borders only featuring young, aggressive men and provocative, alarmist content was normalised.Fake news and doctored videos became increasingly frequent. Leaked company emails showed how editors expected loyalty to the government from all employees, and publishing reports from human rights organisations such as the Amnesty International or the Human Rights Watch became taboo. The national news channel was forced to make several corrections after court rulings determined they had broadcasted false statements regarding opposition politicians.

Distrust characterised the whole system. Even the leaders were subjected to rigorous monitoring; executives, including Miklós Vaszily, the CEO of MTVA, were wire-tapped. In 2018, Vaszily’s position was taken by Daniel Papp, who had already proved his loyalty towards the institution during the Cohn-Bendit scandal.

In the same year, security guards used physical force to remove protesting MPs from the headquarters of MTVA. Referring to the scene as an „act of cabaret”, Viktor Orbán showed unflinching support for the the executives of the public media.

Since then, the public media does not even pretend to be independent; opposition politicians are regularly described as ‘boorish’ or ‘primitive’ by the hosts, whilst speeches of Viktor Orbán are being broadcasted 10-12 times a week. Balázs Bende, the editor for foreign affairs openly argues against the ‘anti-Hungarian and anti-Christian’ opposition, and during a leaked recording, told his colleagues that at the public broadcaster they do not support the opposition coalition, and he advised that anyone surprised by this statement should simply leave.

Bending everyday reality

It was still in the heydays of daily newspapers, when Orbán and Simicska entered the political scene. In the 90s the socialists held a significant advantage within this sector, and therefore, Fidesz’s primary media policy sought to get ahead in the competition.

They saw print media as the key to ruling public discourse.

After winning the 1989 elections, Orbán's first step was to capture Magyar Nemzet— which later became the most prominent conservative daily paper—, and slyly transfer it into the hands of Simicska, thereby laying the foundations of a partisan paper for Fidesz.

While in opposition, Magyar Nemzet and Hír TV (broadcasting since 2003) played a key role in making sure the right wing political block around Fidesz stays together, becoming a safe haven for Fidesz-related public figures and politicians. After Fidesz gained its first super-majority in 2010, Simicska had the financing framework ready; they put loyal people in control of the largest state owned corporations, who then began channelling advertising supporting his media empire. This was the exact same method Simicska later used to propel Metropol to success, a free newspaper, which gained a monopoly over distribution in the public areas of Budapest.

Capturing the daily Magyar Hírlap required almost no effort. The owner, Gábor Széles, kept bankrolling the paper, never giving up hope on becoming a cabinet minister in the Orban government.

It was the Magyar Nemzet that started the first campaigns against academics and other equally powerful actors ; this was the platform where a GONGO launched its semi-regular pro-government ‘peace march’, and the paper soon became the central conduit of the government’s narrative. Thus, it was no surprise that the Magyar Nemzet became the most contentious asset in the Orbán-Simicska war that erupted around 2014. After Orbán and Simicska fell out, the Prime Minister levied heavy taxes on Magyar Nemzet, and turned Gábor Liszkay, editor-in-chief, against the oligarch. In response Simicska changed editorial direction and transformed the paper into a platform for voices critical of the government. No price was too high: afraid of Simicska’s revenge, Orban dedicated untold resources to capture the entire media sphere.

After 2015, Fidesz had two main goals: to recapture all assets taken by Simicska, and to rebuild an even stronger media empire. Orbán established a de facto Ministry of Communications, the Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister led by Antal Rogán. Through this new institution Orbán is able to supervise every single forint spent on advertising by all state and government institutions. He also called on government friendly entrepreneurs to invest in rightwing media platforms.

A new group of media owners were emerging. Árpád Habony, Andy Vajna, Miklós Ómolnár, Mária Schmidt, Tamás Szemerey and Lőrinc Mészáros all took their share of the new media empire. Tabloids, daily newspapers and online news platforms were created one after the other. The government set an annual 25 billion forints budget for the „ministry of communication”, so the new media empire can be sustained through state and government advertising..

The most important step towards the occupation of the print media sector was the establishment of publisher „Mediaworks”.

During the summer of 2016, the company,—still owned by Heinrich Pecina—, bought Pannon Lapok Társasága. By purchasing the publishers of 5 (out of 19) regional newspapers papers, Mediaworks took control over half of the entire regional media sector. At this stage, rumours were already suggesting that the company would soon be bought by Lőrinc Mészáros. Not long before the purchase, Pecina ordered the closure of Népszabadság, Hungary’s paper of record. Fidesz tried to maintain that it had nothing to do with the decision and even during the last days before the acquisition, Meszaros kept denying that it was going to take place.

Later, it became apparent that Pecina and Orbán had met in person and during the ‘Ibiza-gate’ scandal Heinz-Christian Strache, former Austrian Vice Chancellor, had been caught on camera referring to Pecina as the frontman of the Hungarian PM.

Orbán and his circles had long resented Népszabadság, ever since the paper published the first big scandal about Fidesz in 1998; a story about how a couple of companies owned by the party elite were being sold to foreign nationals to avoid paying taxes.

Whilst closing Népszabadság was personal; real political utility was to be found in capturing the regional newspapers. Before the 2018 elections, Orbán assigned the Fidesz-friendly entrepreneurs to take over the other, still-independent half of the regional newspaper market. Pecina took hold of Russmedia, and the international film mogul, Andrew G.Vajna, purchased Lapcom Zrt. with loans provided by the MKB Bank. By the time of the elections, Mediaworks controlled all 19 of the regional newspapers.

This was the first time Fidesz utilised their control over the media authority; the institution had no objections when government aligned actors captured the complete regional media scene.

The advent of the big platform companies reshaped the advertising market, killing newspaper profits, helping the state to become the largest advertiser. Through controlling state advertising Rogan and his team was able to reshape the entire media scene.

Next on the list was Népszava, the historic daily of the former social democrats. Encouraged by Viktor Orbán himself, László Puch, former treasurer of the socialist party , purchased the paper, and the platform started receiving significant state funds. Népszava was later obtained by Tamás Leisztinger, the businessman who had already bought himself into the Fidesz elite through the ownership of a first-league football team - something which stands as a symbol of belonging to Orban’s circles.

While state funded advertisements tripled at Népszava, Simicska’s Magyar Nemzet and the Hír TV (outlets that never had to make ends meet without significant state advertising) were starved to death. It became clear that a potential victory for Orbán would seal the failure of the Nemzet-group. And this is exactly what happened: Fidesz was reelected with two-thirds majority in April of 2018, Simicska gave up, and let his entire media empire fall into the hands of Fidesz by August. Gábor Liszkay and his men showed up at the studios of Hír TV studio and fired the remaining workers of the Simicska-complex during a live broadcast.

A very humiliating and public dismissal, so everyone learns what happens to those who betray Orbán.

Into the unknown

After 2010, Orbán and Simicska started laying plans for the step-by-step conquest of the online media market. Fidesz had a significant disadvantage here; they had no influence over the heavily expanding digital sector, and the ageing party-members were unfamiliar with its inner workings but the party leadership understood its growing influence in politics.

The online news market was ruled by two prominent sites; Origo.hu, owned by Magyar Telekom (Hungarian Telecom, a subsidiary of the German Deutsche Telekom) and Index, which was in the hands of the banker Zoltán Spéder at the time. After 2010, these sites became the primary targets of the government.

Fuelled by the ‘Orbánian’ logics of power, Fidesz never tried to compete with the platforms, provided it could snatch control over them.The political risk of investing in independent media was soon to be understood by the whole economic elite. To stay on good terms with Orbán, one had to keep a distance from the platforms that influenced the public discourse. The market entered into a phase of stagnation: new platforms stopped emerging, investors turned down potential acquisitions. Fidesz has declared their preemptive right over the whole media sector.

Magyar Telekom, owning Origo, one of the most popular online platforms of the days, faced rough challenges from 2010: Orbán introduced taxes for telecommunication, minute-based taxation on calls, and a utility tax of 20-30 million Hungarian forints, halving their annual profits. Their parent company, the German telco giant Deutsche Telekom, tried to intervene in hope of lenience. Letting go of Origo was just a small sacrifice for saving Magyar Telekom, especially since the government was already putting real pressure on the editors. The editorial team fell apart in 2014, when Magyar Telekom fired the chief editor, Gergő Sáling. He was dismissed after articles about the hotel bills of János Lázár, the Minister of the Prime Minister’s Office, appeared on Origo.

Deutsche Telekom decided to sell Origo, especially since the media platform was an outlier within their telecommunications portfolio. Origo was first bought by István Száraz, the businessman from the circles of György Matolcsy, governor of the Central Bank. Nevertheless, Száraz was only the frontman and Origo was soon to be taken by Matolcsy’s son, eventually merging into the Fidesz media empire.

After capturing Origo, Index.hu was the other big player still standing. The owner of the influential site, Zoltán Spéder, was a banker and businessman who had already helped Fidesz during the early 1990s. Spéder had direct connection to Orbán and had built close ties with János Lázár (considered number 2 at the time) by 2010. Spéder convinced the Prime Minister to enable a merger of the “Posta Bank” and several credit unions to create a financial institution that can compete with OTP, the largest bank in Hungary. As the merger started, Spéder had to maintain his position as a government insider, whilst keeping Index from staying too far. The newsroom was facing increasing pressure. In 2011 Péter Uj, the editor-in-chief, left the paper and founded 444.hu.

Spéder’s balancing act was unsuccessful and despite his efforts to keep the Index newsroom under control the government made it clear that such an important platform needed to be reined in. During the last weeks of 2013, Simicska (still allied with Orban) signed an option for the publishing company of Index, in preparation for the complete purchase.

Capturing Index was a plan made by the Orbán-Simicska duo, but their emerging conflict set up an alternative scenario. After 2014, Simicska invoked his purchasing option for Index, and established a trust to control the site. In the same year, Fidesz was reelected, but the new financial framework protected Index and its integrity until 2020. Learning from the takeovers of the past decade, the journalists at Index resigned as soon as new owners showed up, and established a crowd-funded online platform, Telex.

Index was absorbed into the government controlled media empire, after Miklós Vaszily, business partner of Lőrinc Mészáros, and former CEO of the state broadcaster MTVA bought 50 percent of the shares issued by the publisher company. Index has not been completely transformed into a zealous government mouthpiece yet: it tries to reach opposition leaning voters and generate uncertainty. In November 2021, the “new” Index released a story about supposed corruption at the Budapest City Hall run by mayor Gergely Karácsony, an opposition politician. “Index was being used by someone as a platform for attacks against their political enemies” an editor told the press after he resigned over the articles smearing Karácsony.

The war will only end when there is no one else standing. Zoltán Varga owner of the Central Media Group and 24.hu, another large, independent website, found himself in the crosshairs of the government. After several failed attempts to purchase his media portfolio he was targeted by a smear campaign and his phone tapped with Pegasus, the Isaeli made cyber-weapon only government agencies are allowed to use.

Remote control in action

„Their ultimate dream”, was how a government-related political analyst described Orbán and Simicska’s view of TV2 back in 2010. Fidesz has always been suspicious of the commercial TV sector dominated by large international media companies. Since the first channels started broadcasting in 1997 they were viewed as the playground of the liberal Budapest elite, who had little loyalty for Orban’s first government between 1998 and 2002 and some blamed these outlets for the 2002 defeat.

The two largest players competing for the top spot were the German owned RTL, owned by the Bertelsmann group, and TV2 owned by ProSiebenSat1. In 2010, when Orban came to power after 8 years in opposition RTL was hugely profitable while TV2 was operating at a considerable loss, its owner therefore willing to sell.

Today it may seem absurd, but back in those days Fidesz did not have the financial capacity to purchase TV2 for a 10-20 billion forints, especially since international media groups like Discovery Inc. or the Modern Times Group were also angling to buy the channel.

In 2013, Fidesz imposed a new tax on advertisement threatening the survival of TV2, whilst eliminating international competition for its purchase. The same year, ProSiebenSat1 sold the channel in a deal that included an option for Simicska, to ensure Fidesz’s ownership rights for a potential election victory in 2014.

As the Orbán-Simicska fight erupted in 2014, this purchasing option for TV2 became an important point of conflict. When Andy Vajna bought the channel in 2015 - carrying out the wishes of PM Orban-, Simicska aimed to thwart the transaction by openly exercising his right to buy first. He was trying to demonstrate he was still in control.

Later, the extensive legal procedure showed that Simicska’s option was only a show-off; he had neither the ability nor the capacity to buy TV2, especially considering the increased hostility of the political environment.

Once in power, Orbán became unbeatable. He had access to unlimited resources and showed an unsettling willingness to sacrifice anything in the name of victory.The final takeover was completed by Andy Vajna in 2015; receiving loans from Eximbank—supervised by the Ministry of Foregin Affairs—and MKB Bank, the film producer turned business mogul only had to chip in 2.5 billion forints (less than 14% of the value of the acquisition). Since the captured TV2 was always going to be subsidised with state advertising, there was no question about the profitability of the deal. The Cabinet Office in control of state advertising spending allocated more and more money every year. The volume of state advertising on the TV2 network went up from 5.5 to 23.7 billions by 2020. This was more than 10 times the profit generated by RTL, which had the same amount of viewers.

The influx of state money enabled the expansion of TV2 Media Group acquiring local assets and starting ventures in neighbouring Slovenia. There is enough state money to go around to also finance the lost and recaptured Hir TV and channel funds toward ATV, which, while sometimes critical of the government understands the limits of “independence”

A personal toolbox

The early phase of the media capture was characterised by the deceitful nature of Simicska’s methods. Everyone knew about Magyar Nemzet functioning as a partisan newspaper, but the editorial team maintained the pretence of neutrality. Even the clandestine nature of the deals around the purchasing options for Index and TV2 demonstrated a level of humility. Expansion was silent and measured .

The end of the Simicska-era did not only bring new owners, but a whole new M.O.. Orbán spent less time disguising the new realities.

In this paradigm the government not only maintained a highly partisan media empire, but established or captured a complete arsenal of platforms to support Viktor Orbán’s position. And all this manoeuvering was funded by the taxpayers. In 2015, the state directed 25 billions of forints to the media empire through the Prime Minister’s Cabinet Office. This amount increased to 35 billion the following year, and then to 50 billion. Since 2020, the Fidesz-controlled media companies have a cumulative annual income of over 70 billion forints. Antal Rogán, and Árpád Habony, Orbán’s unofficial advisor, refined the propaganda machine; they launched massive ad-campaigns against the Hungarian opposition, George Soros, refugees, and the EU, especially ironic, since subsidies from Brussels contribute greatly to the financing of the media empire.

Emotionally charged political campaigns always played a key role in Fidesz’s communication strategy, but TV2 took the fearmongering to another level. The Vajna-owned, state-sponsored hired paparazzo and based their stories on reports from the tabloid press. The platforms were entirely weaponised.

During the 2018 elections campaign, photographers followed Zoltán Spéder after he fell from grace, and Gábor Vona, one of the opposition PM candidates. After a high school student, Blanka Nagy used harsh words at an anti-government, she became the target of a concentrated smear campaign, with one pro-government opinion leader calling her a “slut”, an outlet publishing upsikrt photos of her, while others reported on her grades. Péter Juhász, another one of Orbán challengers, was said to be abusing his partner. Ákos Hadházy, the anti-corruption activist and independent MP was accused of harassing a neighbour leading to the man's death. The wife of Péter Márki-Zay, leader of the 2022 united opposition coalition, was blamed for the death of a newborn baby.

In all of these cases, the publishing outlets later had to issue corrections and apologies and in some cases pay damages after courts determined that the reports were made up.

Despite the personal nature of the acts, the aims were political. The attacks were meant to discredit and intimidate anyone with political ambitions. Those wishing to participate in Hungary’s public life should prepare for the worst—the government’s message was crystal clear.

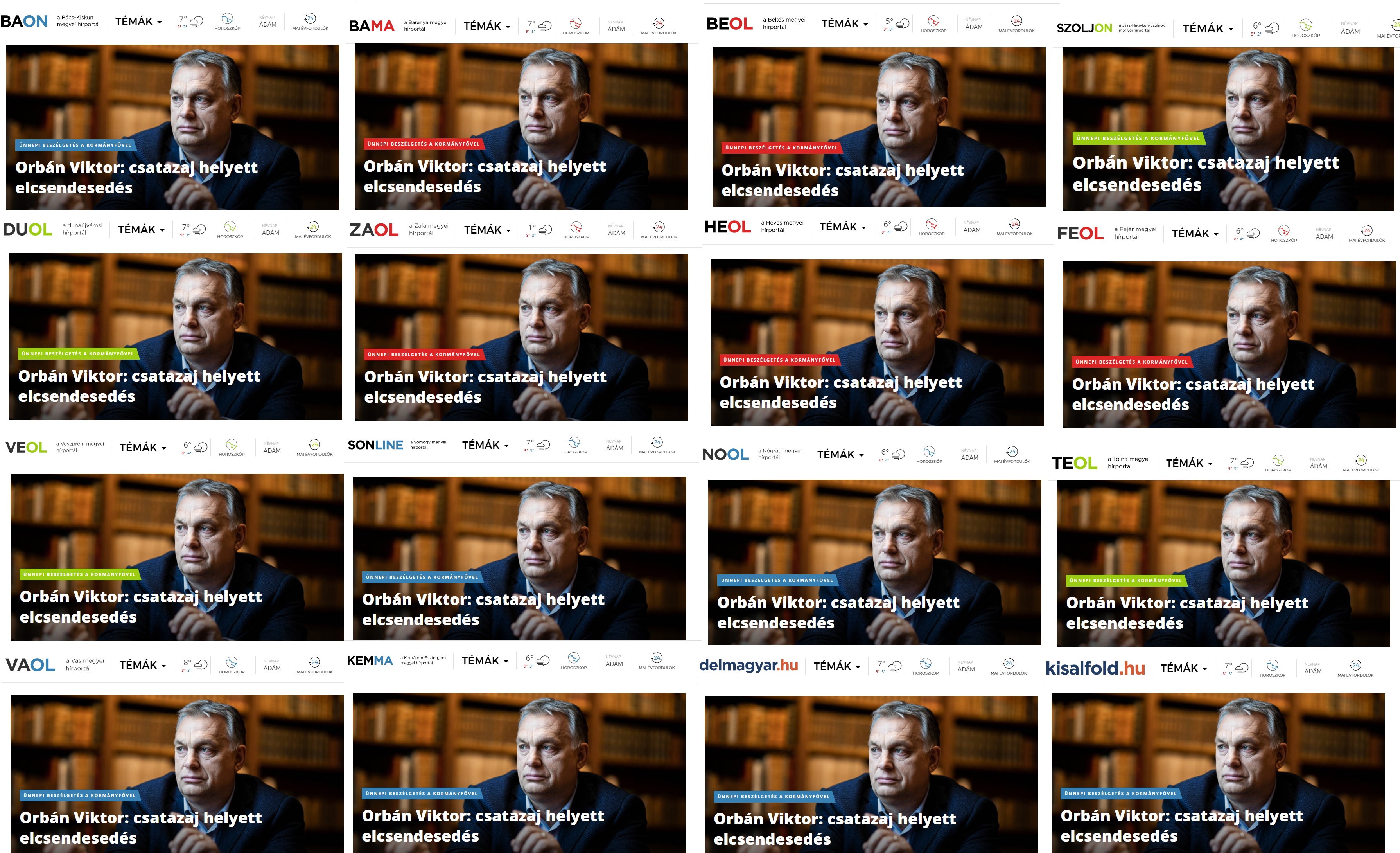

No one had illusions about the purpose of the newly built media machine anymore.After winning his second super-majority, Orbán decided to lay his cards on the table. In November 2018, billionaire owners of over 400 media outlets suddenly all decided to gift their entire media portfolios to the Central European Press and Media Foundation (CEPMF - KESMA). A week later PM Orban signed a decree exempting this mega merger from regulatory oversight.

Mediaworks, the publisher of the 19 regional newspapers and other outlets (previously owned by Lőrinc Mészáros), a whole network of regional radio channels, the Nemzet-group, Origo, the conservative-nationalist Mandiner, Mária Schmidt’s Figyelő, a cluster of Fidesz-tabloids and even some of the leftist papers formerly owned by László Puch became part of the umbrella organisation. Altogether, the foundation oversees 476 different outlets. The only significant companies in the pro-government media sphere that are not part of CEPMF is the TV2 network, Index ultimately captured in 2020 and the state media conglomerate MTVA.

In addition to providing a new financial framework, establishing KESMA was a political statement. He has publicly proclaimed the whole press as his personal set of political devices, no more frontman, clandestine deals, pretence.

In December 2018, a week after the CEMPF deal was done PM Orban signed a decree exempting the mega merger from regulatory oversight designating it “of national strategic interest”

Editors within the pro-government media sphere view themselves as political actors, soldiers rather than media professionals bound by journalistic ethics. They don't care about facts, routinely falsify stories and even ignore the verdicts of the courts when they are forced to issue corrections. In multiple rulings various courts have determined that Origo and TV2 were knowingly, purposefully fabricating stories to mislead their audience. The verdicts spell out how their activities have nothing to do with informing the public and everything with manipulation of public opinion. After all, this is their job, it’s what the regime expects of them.

Translation by Lili Lénárd.