Masked men attacked the Roma laborers just as the police officer had advised

“You'll die, filthy gypsies! Everyone on the ground!”

This was the first thing the public works laborers heard when men wearing masks attacked them near the creek. There were eight assailants armed with baseball bats, crowbars, some brought knives, pepper spray and CO2 pistols.

A younger victim was sprayed as he tried to flee the attack. He fell on the ground and assailants opened up on his legs with a crowbar, breaking one. He was held down, and one of attackers whispered

“You'll die today, we will kill you”

before trying to cut his ear off. When he raised his hand in defense, the knife punctured one of his fingers. The beating continued. His father, who was also among the group of workers, got it just as bad. After he fell, they attackers broke his arm with the crowbar. While beating him, they yelled

“We’ll burn your house down while you’re still inside, filthy gypsies!”

*

All of this happened near a small village in northeastern Hungary in August 2014. To protect the victims, we changed the names of the people involved.

*

Later that day, Kristóf, the local man who led the gang of attackers, was arrested. His victims were able to identify him based on his voice and a unique tattoo. His accomplices were never found. All together, Kristóf spent three days in custody. He got a suspended sentence in May 2016 after a judge ruled the beating of the Roma laborers was not a hate crime. The investigation revealed that the attack happened just as a local police detective proposed it should a few days earlier. He wasn't charged for his involvement, and he remains a detective to this day. Two months after the attack, the far-right group “Betyársereg” (Army of Outlaws) organized a march in the village. On their website, they celebrated clearing “the anti-social creatures” out of the area.

Weight Lifting and a Synthesizer

“We were neighbors for more than ten years. We had a good relationship. He laid these tiles in our kitchen, and we helped them when their electricity was cut. We had no problems with each other.”

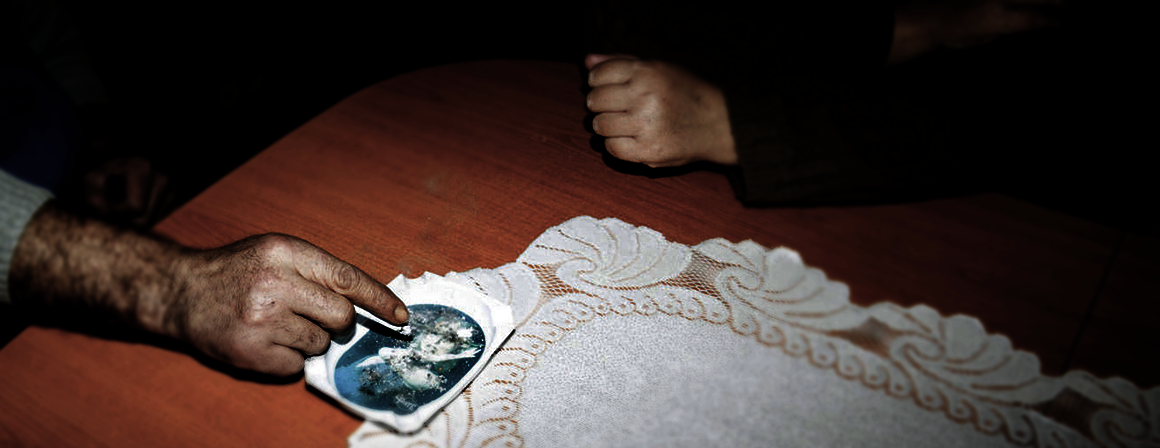

This is what Károly, the man whose arm was broken during the attack, says about the only known assailant. Karoly and his wife are both employed. Károly now works in a vineyard, his wife is a public works laborer. They have an orderly one-storied home, heat with a wood-burning stove, and do not live in extreme poverty, unlike many of their fellow Roma in northeastern Hungary.

Neither Károly nor his wife can say with certainty when the relationship with their neighbor, Kristóf, soured. They said conflicts began after Kristóf started lifting weights. Both remember the first real argument took place after they bought their 16 year old son a synthesizer for his birthday. Their boy’s practicing bothered their neighbour.

Kristóf later moved. During the trial, Kristóf told the judge he moved because of the bad relations with his neighbors. Károly and his wife say Kristóf moved because he inherited a better house in the village.

Not long before the attack, Kristóf and his friend were drunk and started to urinate in front of Karoly’s house while the family was in the garden. They told him to turn away and an argument erupted. Soon after, Károly’s wife and Kristóf’s girlfriend got in fight outside a local store. Kristóf’s girlfriend made derogatory comments about Károly’s disabled daughter. Károly’s wife responded by slapping her. The police got involved.

The attack against the public works laborers took place a week after this altercation.

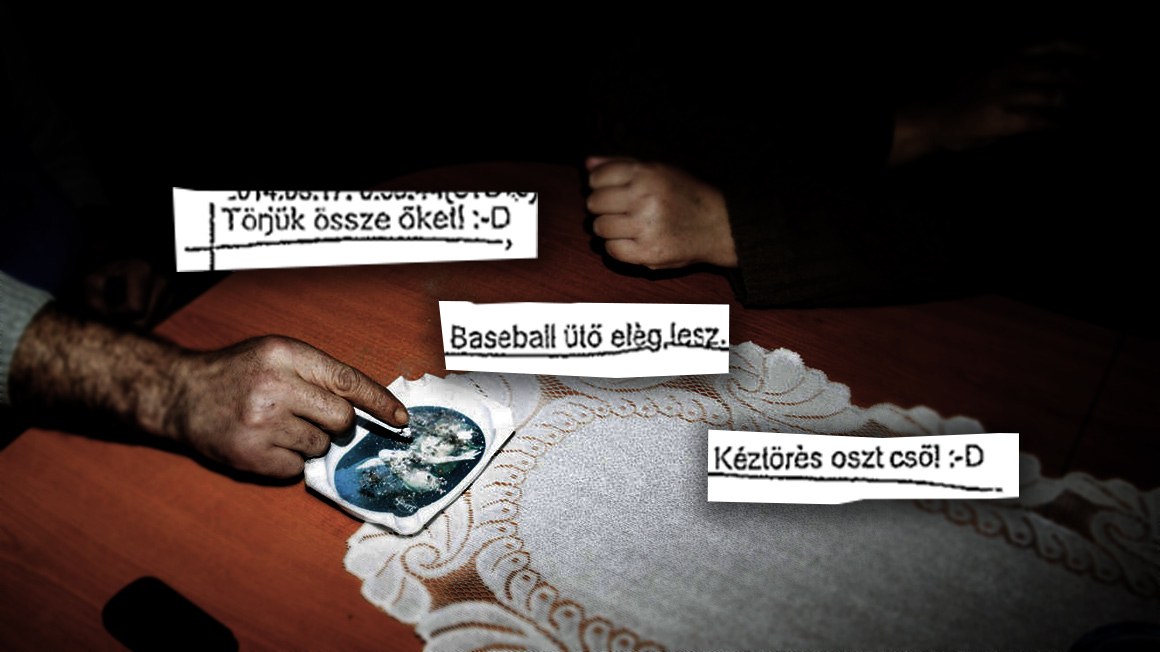

Broken hand and it’s done :-D

One more thing happened between the two incidents. Kristóf would occasionally lift weights with a local detective. They also kept in touch over Facebook. During the investigation, Kristóf’s phone was confiscated and the police looked at his messages.

The weight-lifting detective friend was kept abreast of the evolving conflict. Kristóf’s girlfriend asked him to provide her with pepper spray. She said she needed it because she had to walk past Károly’s house every day. Later, the detective asked for Károly’s full name and address.

“I’ll check to see whether there is anything out for them right now. I’ll let the watch commander know to put them in their place,”

he wrote.

“That would be good,”

Kristóf’s girlfriend replied.

A few minutes later, the two discussed assaulting Károly’s family.

“Let’s crush them :-D We’ll dress up in black clothes, put masks on, and take care of it quickly. It won’t even last a minute. All we need is a baseball bat. A broken hand and it’s done :-D. They won’t even know who did it.”

Kristóf’s girlfriend responded,

“It needs to be done. These kind won’t learn any other way.”

No malicious intent or racist motive

The first investigation was closed in January 2015, four months after the attack. The police were satisfied with having charged Kristóf, and resigned to the fact that they couldn’t identify the other assailants. A second investigation was launched after the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU) turned to the Prosecutor General. The HCLU managed to have the county police department look further into the attack to determine whether it was a hate crime — something the first investigation did not even consider.

After a relatively short trial, a verdict was issued in May 2016. It went into great detail about the attack. Seven public works laborers were on the job near the creek that day. Of them, only four people were beaten: Károly, his son, and two other family members. The three remaining workers were allowed to flee the attack.

“Not them, only the other four,”

is how court documents show Kristóf instructing the masked attackers. As Károly’s family’s bones are being broken, Kristóf says

“You know why this is happening.”

The court ruled none of the serious bodily harm was actually caused by Kristóf, but instead by the remaining unknown assailants. He was only charged as an instigator and co-perpetrator of the assault.

Despite the beating opening with “You'll die, filthy gypsies!”, the judge ruled the attack “was not motivated by racism, but instead by a personal conflict.” According to the judge, this is proven by the fact that not all public works laborers were attacked, only Károly and his family. The judge also determined there was no malicious intent either, and concluded the attack was based on personal revenge and anger.

Kristóf gave no statements during the investigation and denied any involvement in court. He blamed Károly’s family for turning him into a suspect. He also said Károly’s relatives had earlier threatened his own family with a knife, and he wasn’t even in the village when the workers were attacked.

The court didn’t buy the alibi and decided he was indeed the leader of the attackers. Since the judge found no evidence of a racially-motivated hate crime or malicious intent, Kristóf was handed a two years suspended sentence and put on four years probation. During the investigation, Kristóf was locked up for three days and then was kept under house arrest for nine months. A date for an appeal has not yet been finalized.

Two months after the attack, in October 2014, the extremist group “Betyársereg” held a march in the village. Regarding the march, Betyársereg wrote that one of their local friends

“was threatened by creatures whose genetic programming prevents them from being part of normal society. The response was swift and successful. The anti-social creatures have been cleared out.”

The court did not consider this fact — even in light of a message sent to Kristóf’s girlfriend from one of her friends on the morning of the attack:

“Hey, did your man invite Guards [another extremist group not unlike Betyársereg] to the village?”

“Whatever are you talking about? What is a Guard? *.* :@”

responded Kristof’s girlfriend at the very same moment as the group of people donning masks attacked the workers. The court did not concern itself with the reference to “Guards” arriving in the village before the attack.

There was a smiley emoticon, so he must have been joking

An inquiry into the detective’s involvement began after investigators looked at the message on Kristóf’s phone. It started in December 2015, 16 months after the attack.

“The Facebook chats between the police officer and the girlfriend of the suspect which took place five days before the attack show that a recommendation was made as to how to handle the conflict. This is especially significant in light of the fact that the crime on August 22, 2014, was committed just as the police officer had advised.”

This was written by the deputy captain of the county police department to the detective’s immediate supervisor. The issue was tossed around between various agencies until August 2016, when the investigating prosecutors decided the detective committed no crime.

The investigating prosecutors emphasised that the detective’s chats ended with a smiley emoticon and the recipient told them she did not take the messages seriously.

Kristóf’s girlfriend had also claimed she never forwarded the detective’s recommendations to anyone and her mother-in-law got her the pepper spray, not the police officer.

Furthermore, the detective was not on duty on the day of the attack. His telephone was not detected by the cell phone tower near the scene of the crime, and internal police records do not show him looking into Károly’s family as he had promised while chatting with Kristóf’s girlfriend.

In light of these circumstances, the police officer was not charged as a co-perpetrator or instigator, nor was he charged with abuse of power. In December 2016, the police department refused to comment on whether the officer was reprimanded in any way, but they did admit that he continues to work as a detective just as he had before the attack took place.

There’s no way a Roma person could get away with something like this

Károly and his son spent months recovering from the beating. Károly’s wife had to bathe them and help them use the toilet. They say they have healed physically, but not emotionally.

“We don’t want to move past this and forget about it. We want those who did this to us to be brought to justice. At least some of them should be in jail.”

Károly, his wife, and the whole family was present for the sentencing. They were frustrated when they learned Kristóf would not go to prison. They know a personal conflict was behind the attack, but also think racism had a role in it. From their point of view, personal conflict and racist motivation are not mutually exclusive.

What hurts them most – and what they feel to be the greatest injustice – is that if a Roma person would have committed these crimes, they would certainly be sitting behind bars.

We spoke to a number of legal experts about the investigation, Kristóf’s sentence, and hate crimes. They were inclined to agree with the victims about personal conflicts and racist motivations not being mutually exclusive.

His crime was being born

“If the victim could be replaced with someone else from that group, if they are being attacked simply because they were born, then we are talking about a hate crime,”

says Petra Bárd of the National Criminology Institute (OKRI).

This isn’t true in Kristóf’s case. He did not want to attack Roma people in general, but instead targeted Károly and his family to get revenge for the earlier conflict.

European Court of Human Rights case law shows that attacks can have multiple motivations. They can be both racist and personal, and the stronger of the motivations must be taken into consideration. Racism certainly played a role here. The seven accomplices obviously had no personal conflict with Károly’s family. They wanted to attack Roma people. It was no coincidence they yelled “You’ll die, filthy gypsies!” during the attack. They attacked all of the workers before Kristóf finally told them precisely who to hit.

In this regard, the Hungarian court’s ruling did not establish Kristóf’s responsibility for inciting a racist attack.

The verdict refers to a crime of anger and revenge, but this was not some simple bar fight where someone picks up a bottle in anger and smashes another person in the head with it. This attack was premeditated. Kristóf had to plan: seek out accomplices, acquire weapons, find out when and where his intended victims would be together, and where the beating could take place uninterrupted.

Roma people are being prosecuted by very law meant to protect them

Between the spring of 2008 and autumn of 2009, a four man gang murdered six people, including one child in Hungary. The murders were meant to scare the Roma people. In 2008 and 2009, extremists attacked attendees of the Budapest Pride parade.

Politicians were eager to create the impression they were doing something about these cases, so they started tinkering with laws dealing with hate crimes. They deemed the protection of LGBT people to be politically unpopular, so instead of focusing on sexual orientation, they inserted blanket protections for “certain groups of the population”. Petra Bárd of the National Criminology Institute says this was a mistake.

Bárd has researched how this rule is being used in Borsod county where a large part of Hungary’s Roma population lives. She found that the conviction rate of Roma in such crimes are higher than in cases involving non-Roma.

“The fact in Borsod is that the rule meant to protect Roma from racially-motivated violence does not serve its intended function because it is only used in a very small number of cases, and it is not used primarily in the defense of vulnerable groups,”

Bárd wrote in one of her studies.

The very rule meant to protect the Roma is being used by authorities against them.

While it is difficult to compare individual cases, this is where the majority of jurists we spoke to can agree with Károly’s family:

If Roma people were to commit the same crime as Kristóf and the masked attackers, they would surely end up in prison.

Eszter Jovánovics, director of Roma Programs for the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union, says there are cases even today in which Roma people have conflicts with members of the outlawed extremist Hungarian Guard, and the Roma people are convicted under the hate crime legislation. According to courts, belonging to a banned extremist group means belonging to a “certain group of the population”, a protected class.

We don’t have racial violence, we never have

When discussing racial violence in general, OKRI’s Petra Bárd, Eszter Jovánovics of Hungarian Civil Liberties Union, and Borbála Ivány of the Hungarian Helsinki Committee all say it’s as though law enforcement agencies in Hungary are unwilling to recognize the problem exists.

In one study, Petra Bárd examined incidents between 2009 and 2013 and found prosecutors opened only 136 such cases in five years. She considers this number to be quite low. There are about 62,000 hate crime cases registered in the UK in one year — ~2,200 times more than in Hungary. While it is true the UK’s population is six times greater than that of Hungary’s, it’s unlikely the British are 2,000 times more racist than the Hungarians. The reason for the higher rate is probably because UK law enforcement agencies are much better at detecting hate as a motive.

Borbála Ivány says Hungarian law enforcement agencies like these low numbers. They think it reflects well on the country because the data indicates there are no hate crimes in Hungary.

“We’ll put in a greater effort when we see an increase,” is how law enforcement officials and prosecutors react to the subject. This is a perfect defense because they won't notice more of these crimes until they put more effort into detecting them. One county prosecutor has even proudly boasted that they have never had a case of racial violence.

In 2013, the deputy Prosecutor General ordered a tougher stance against hate crimes. Experts said this tougher stance mainly applied for hate crimes committed against Jewish people. When Roma or LGBT people are targeted, the tough stance of the authorities is harder to detect.

When Rabbi József Schweitzer was insulted on the streets of Budapest in 2012, President János Áder visited him personally a few days after the incident. Meanwhile, not a single politician has taken the effort to visit Károly’s family.

They're better off not calling it a hate crime

The justice system does punish those who commit hate crimes, the issue is that they are charged with simple assault and battery, and the racist motivation is rarely revealed.

Petra László, the camera women who kicked refugees near the border with Serbia, was convicted of misdemeanor assault. In a separate 2016 case, a court ruled that the beating of a refugee from the Ivory Coast started off as a hate crime but later devolved into misdemeanor assault. There, too, the assailants received a suspended sentence.

Petra Bárd says these types of cases aren’t clear cut, often times the motivations are mixed. They can be personally and racially-motivated at the same time.

Both Bárd and Borbála Ivány from the Hungarian Helsinki Committee suggest the charges that end up being pressed are often decided by the actions of the first responding police officer. If the police report is lacking in indicating a racial motive, then the police and prosecutors will avoid pursuing charges along those lines.

The work of police is evaluated based on successful investigations, and prosecutors are judged based on the number of guilty verdicts. They are more likely to pursue what sticks, for example, assault and battery, instead trying less certain charges related to hate crimes simply because they’re concerned about their own professional advancement.

Since 2011, every county police department has a professional hate crime expert, Ivány says. This person is supposed to pay attention to criminal cases where there is possibility that a hate crime has occurred.

Ivány and Eszter Jovánovics of the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union are members of the civilian Workgroup Against Hate Crimes. They often meet with employees of the national police and interior ministry to go over best practices for identifying hate crimes.

Following in the footsteps of the UK, the workgroup has prepared a manual for law enforcement personnel to help detect and assist in cases where hate crimes have occurred. In the UK, police are required to treat any incident as a hate crime even if only one of these indicators has been met.

According to Petra Bárd’s research, the Finns, Dutch, Swedes, and British are the best in Europe when it comes to combating such crimes.

(You can see the original Hungarian article here. Benjamin Novak of the English-language Budapest Beacon translated this report.)