Abused by a priest, faced with charges by the cardinal's aids, and kept behind bars without apparent cause

When the leaders of the Hungarian Catholic Church filed their charges in the summer of 2019 they must have known they had a lot at stake. That if their plans didn't go through they would be the ones within and outside the Church, at home and abroad, who not only turned their backs on a victim but also went after him. Among the tens of thousands of cases of molestation in the Catholic world, I have not found one where a bishop and an vicar general took legal action – against a victim. What is even more groundbreaking is the involvement of a cardinal elector, a magistrate of the universal Church that claims to be the most vocal defender of victims, whose name has been mentioned several times as a potential candidate for the papacy.

The leader of the Catholic Church in Hungary, Cardinal Péter Erdő, Archbishop of Esztergom, in a strange interview in 2021 repeatedly and emphatically tried to distance himself from the case of the molested man, Attila: “The diocese is not in any legal proceedings with this individual [...] this is not a matter for the diocese”. But the court documents make it clear: one of the complaints was made by a deputy of Erdő “in the name and on behalf of” the archdiocese led by Erdő. The other was made by his auxiliary bishop.

This English-language article consists of two parts: an edited version of two articles (1; 2) from 2021 and a summary of subsequent developments.

I will first present the proceedings of Church historical significance through the court documents and the included witness testimonies, and then separately the coercive measure of the authorities of August 20, 2020. I would have also wanted to give space to the views of Péter Erdő and the magistrates concerned but they did not even respond to my requests.

No records

In the past two decades about 20-30 Hungarian Catholic priests have been investigated for sexual abuse, or rather that is how many I have been able to find information about as there have been no comprehensive church or state investigations. There are no official statistics on the topic and most dioceses do not publish data even when asked.

Attila was the first victim in Hungary to fight in public for the Catholic Church to face up to its mistakes. He was molested by a young priest, Father Balázs, more than 20 years ago. As a teenager he told this to György Snell, who later became auxiliary bishop of Budapest, and to György Udvardy, vicar general of the archdiocese of Esztergom, who later became archbishop of Veszprém. There were no records taken, no official investigation opened, the priest denied the allegations and his immediate superior – as it later turned out – covered up for him, knowing about an earlier affair of Father Balázs but keeping it quiet. Instead of the victim the Church magistrates believed the perpetrator who was thus able to keep on groping young boys, reaching into their pants and touching their genitals for the next ten years.

It is difficult to estimate how many children in Father Balázs’s care may have been molested, but according to our information, the Church is aware of more than twenty complaints. These victims were mostly from his congregations around Budapest and it is unknown what happened to the thousands of participants in the camps organized by Father Balázs, to the most vulnerable and often disadvantaged children. In any case, the actual number of victims may be much higher than twenty since it is common experience everywhere that only a fraction of children (and parents) report abuse.

In 2015, about ten years after the first unsuccessful complaint Attila went to the Archdiocese of Esztergom again. Father Balázs still denied it, but this time a formal procedure was launched with witness statements and records. This was now led by László Süllei, the right-hand man of Cardinal Archbishop Péter Erdő who was the office director from 2002 and then vicar general of the archbishop from 2011. According to Attila, the procedure was not transparent and often forced him into humiliating situations, but once several other victims of Father Balázs started coming forward, the archdiocese proposed to the Vatican to open an ecclesiastical criminal investigation. Rome's response was that Father Balázs should avoid contact with minors and that the child-molesting priest should be “scolded”.

In June 2016, Vicar General Süllei sent a report to Rome: in three cases he saw evidence, in Attila's case a high likelihood of “what appears to be erotic, if not explicitly sexual abuse”. The response of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith was for Péter Erdő to impose a severe punishment – but not a final one: it would be excessive to relegate the priest to secular status. In September, the Cardinal banned Father Balázs from priesthood for ten years. Nothing was communicated by the archdiocese about the priest's story who until then had regularly appeared in the media, apart from an internal circular. The victims were not informed either because – even though they could and later will do so – this was not a requirement. Neither the faithful nor the campers would know what happened to their priest.

The story would probably have ended there and then if Attila had not gone to the media months earlier. After the publication of the Index.hu article in October the wheels were set in motion. A parish priest reported that several children were making similar allegations. Only then was Father Balázs also banned from secular duties. Four parents came forward about their children, then another witness, and another. Süllei filed a report to the police because these cases were not yet statute-barred, provided the parents' information, but they refused to seek secular justice.

Finally, Father Balázs was summoned by the archdiocese and wrote a letter to Pope Francis asking for his laicization. The Holy Father did eventually defrock him but this was not made public.

I first came into contact with Attila when I started a series of articles on clerical abuse. Three years after the removal of the offender the victim was still there with the archdiocese refusing to acknowledge him as a victim, or even apologize to him. Several Western prelates, and even the Pope, met with victims in person, but Péter Erdő refused to do so and his increasingly reclusive office did not even inform Attila of the outcome of the proceedings launched over his molestation.

Hide and seek with the Cardinal

In the spring of 2019, Attila made another attempt: he sent a letter to György Udvardy, the former vicar general, to whom he had first reported the events a decade and a half earlier. But when he finally received a reply it was hardly gracious. As we wrote at the time, he was upset that the then bishop of Pécs was attacking and questioning his claims instead of cooperating. He could not understand why, if the Vatican investigation already concluded that Father Balázs had committed sexual abuse, he, who had first reported it, was being treated as if he was lying.

After this, Attila took the plunge and did things that might have precedents abroad but never in Hungary: he made an audio recording of his conversation with Bishop Snell and even distributed flyers in the St. Stephen's Basilica, the most important Hungarian church where Snell was the parish priest.

We reported on this on the evening of June 3, 2019, on 444.hu. The next day, Vicar General Süllei sent an official letter and, after three years of waiting, finally informed Attila of the laicization of his abuser. In the same letter Süllei assured Attila that Bishop Snell, who in the audio recording seemed still very dismissive, had offered him his “spiritual assistance”. When the surprised victim asked the latter about this, Snell did not even reply but sent a message through his secretary saying that “whatever Father Süllei had written and promised in the name of the bishop should be kept by him!”.

Attila went to the Basilica on the same day, the afternoon of June 4, for a solemn mass celebrated by Péter Erdő. According to his later testimony he was hoping that at the mass, which was broadcast live, the Cardinal would apologize to him or to the victims in general. This did not happen and Attila tried once again to talk to Péter Erdő to whom he had written letters in vain for years and for whom he had waited in the Primate’s Palace until they called the police on him.

This time Péter Erdő decided to flee the scene. Contrary to the original plans, the cardinal did not leave the cathedral along the line of worshippers after the mass but snuck out by the sacristy. Several of Erdő’s subordinates gave detailed statements to the police about the incident: according to them, they had been watching Attila the whole time but he did not do anything disturbing in the Basilica. So why did his presence cause “alarm”? As an employee of the diocese, an eyewitness to the police investigation put it, “He gave the impression that he would walk up to the altar at any moment and disturb the liturgy.”

The Hungarian Primate, a Cardinal of the universal Catholic Church, was “evacuated” from a church so that he would not have to be confronted with a victim of a priest. According to the testimony of one of Erdő’s subordinates, Attila was waiting at the side of the cathedral next to the archbishop's service car, so the prelate was led out of the sacristy through a side door and was driven from the scene in a different vehicle.

The next morning, on June 5, the priest of St. Stephen's Basilica, Attila's childhood mentor, György Snell appeared at the 5th District Police Station. The auxiliary bishop reported Attila to the police and the police immediately opened an investigation on suspicion of harassment.

The referenced legislation is Article 222 (1) of the Penal Code: “Whoever, with the purpose of intimidating another or of arbitrarily interfering with the private life or the daily life of another, regularly or persistently harasses him/her, shall be punished for a misdemeanor by imprisonment for up to one year, unless a more serious offence is committed.”

Snell gave the following statement to the police: Attila “has been harassing me for some months. He shows up in person at the Basilica. When he approaches me in the Basilica he wants me to get Cardinal Péter Erdő to apologize to him and to the others for the molestation by [Father Balázs] many years ago.”

The complaint was not made public but according to my clerical sources there was still a tense atmosphere in the archdiocese. Attila told his story on the most popular morning show with Balázs Sebestyén and then the pro-government daily Magyar Hírlap published an opinion piece on it:

"The chatty feud-monger (...) is understandably used by the liberal media and their sponsors. The aim is clear: to weaken Christianity as well as Europe, the continent they want to transform by all means into an open and vulnerable one."

So in the two weeks following the publication of the 444.hu article in the first half of June 2019 the Archdiocese of Esztergom presented a rather chaotic picture:

- the cardinal sneaks out from the cathedral through a concealed route;

- the auxiliary bishop files a harassment complaint against a victim who was molested by one of their priests;

- the two leaders of the archdiocese, Süllei and Snell, send messages to each other through the victim;

- and all the while the clergy and the faithful wait in vain for guidance, the archdiocese and the archbishop, Péter Erdő, remain silent.

In the following weeks two plans to deal with this embarrassing situation were hatched in the Cardinal's entourage. One idea focused on legal redress and deterrence, the other on presenting their own narrative. As one of my ordained sources put it, the saying in the Archbishop's Palace was that it is difficult to defend against lies when the truth cannot be told. That's why it was necessary to leak the documents of Attila's case to the right channels “directly in line with the Cardinal's intention”.

The two parallel plans came to fruition at the same time: on August 20, the police arrested Attila in front of his house and the panic-struck man was held at the police station until the end of the solemn mass. And on August 21, an article based on internal documents was published, the author of which reassured everyone that Attila was wrong, “there was no cover-up”.

Mr. Superintendent, stop him!

But let’s back up to a month earlier! On July 15, the still disgruntled Attila sent a text message to Vicar General Süllei: “If you do not apologize in an official letter or in public for the irregularities of your case handling, if you do not investigate Udvardy's case handling in 2003, then I will go public, at Udvardy's confirmation or at Erdő's programs, at every occasion from August 1 I will keep asking them in person at the ceremonies. Think about it.”

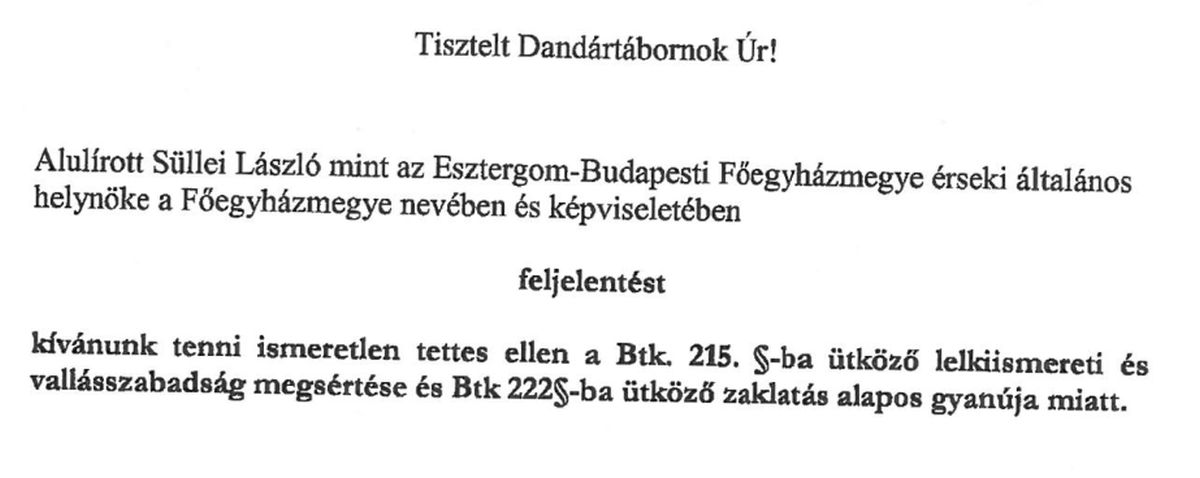

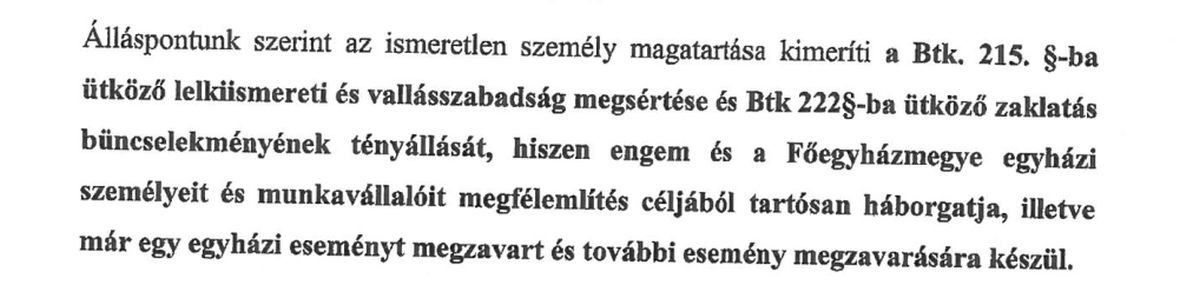

In fact, Attila has never disrupted any ceremony, neither politely nor rudely, not in 2016, nor – spoiler alert – at any time since. In any case, after about a week's pondering Süllei wrote a letter dated July 24 to the Budapest Chief of Police, filing a complaint “in the name and on behalf of the archdiocese” for violation of religious freedom” and for “reasonable suspicion of harassment”.

But it didn't end there. The leaders of the archdiocese made more and more accusations:

- In June, Bishop György Snell filed a private complaint of harassment,

- in July, László Süllei as a representative of the archdiocese, for violation of religious freedom and harassment, while

- in August, Süllei filed a private petition asking the police to take action for “harassment, defamation and threats to obstruct religious freedom”.

Since the police only took the harassment charge seriously, for the sake of simplicity we will not cover the rest either.

But exactly what punishment, what coercive measures did the church leaders seek? In the case of Bishop Snell, the answer appears to be simple: “I request that the authorities take measures, if possible, by means of a restraining order, to ensure the normal functioning of the Basilica services and the parish”. He repeated this in his second police statement.

In the case of Süllei, it is unclear what the purpose of the complainant was in the first place. In his second police statement, he says, among other things, that Attila “spreads defamatory claims about him”, “harasses the Church, wants to disrupt liturgies, is blackmailing us”, “keeps me in emotional blackmail with messages he sends to my personal phone number”. We'll come back to this later as we have the exact wording and number of messages that Süllei considers having exhausted the definition of blackmail and harassment, but for now the question is: what was Süllei trying to achieve? In his first letter of complaint he writes: “I respectfully request the Chief Superintendent to open an investigation and prevent the person in question from disrupting any church event or liturgical program.”

According to his testimony a week later, the leadership of the archdiocese feared that Attila would disrupt church events, the cardinal’s programs and big celebrations – and asked the police to prevent this. However, Attila has never disrupted any event, let alone in a way that violated the law and certainly not at a major ceremony. He did indeed write a few emails and text messages about his intention to speak at masses but is there any authority in Hungary that would take coercive action against a man with no criminal record for his intention to peacefully speak up?

As the end of August festivities approached, Attila was still not informed of any ongoing investigation against him. Yet, had he been questioned it would have been clear that he was not sure it was a good idea to speak at the mass in the first place and by mid-August his focus had shifted to other, more serious problems. He had just found out about his mother's incurable illness, which meant that he was not planning to go to churches but was organizing a family vacation abroad, which they both knew would probably be their very last together.

The leaders of the Hungarian Catholic Church, on the other hand, still had to contend with the prospect of a PR disaster if a victim of a priest appeared at, say, the Procession of the Holy Right, the most spectacular religious event of the year, and yelled something into the live broadcast. Or if he appeared at the Basilica, in the presence of foreign notables and the President of the Republic, or even the Prime Minister.

Péter Erdő’s subordinates tried everything: they filed complaints and submitted a private petition. Although he did not say so explicitly, the cardinal made it quite clear that they were worried about public dignitaries and that they had also told the police about Attila specifically regarding the August 20 celebration: “the individual had sent messages that he was planning to disrupt holy masses. And the holy mass is understandably not indifferent to us. It should be noted that the preparation of the August 20 services is not only a task for the Church but also for the Counter Terrorism Centre (TEK), for instance, since public dignitaries are also participating in the celebrations. Therefore, if the diocese learns that someone wants to disrupt the ceremony it will obviously report it to the police,” Péter Erdő told Válasz Online in an interview in January.

But as much as the archdiocese was concerned, no decision was taken to restrain Attila, and there is no documentation of any measures being taken in connection with the celebration. Officially, we have to accept that the events described below happened by complete coincidence on this particular day and that the police were not fulfilling a written request addressed to them by the Catholic Church.

August 20.

It was a public holiday and Attila and his partner got up late. They left their home in Rákoscsaba around 11 a.m. to buy breakfast at the local grocery store. They were walking back home when, with an action-movie-like speed, two vehicles, a civilian and a service car, cut in front of them. Five police officers surrounded them and stopped them for an ID control – Attila told 444.hu. They let his partner return to the apartment and asked him if he knew why they were there. “I guess because of the Church” – said the victim-turned-suspect. “That is a good guess. You need to come with us.”

They took him to the 17th district police station where Attila, who was “cooperating all along” according to the report, sat in the corridor for a while, still not knowing why he was there. Then he was locked in a cell. This is not unprecedented in police arrests but it was still traumatic for Attila who did not know why he had been brought in, what he was being charged with and how long he would be behind bars. Having a history of panic attacks, the confined cell was not an ideal environment for him to spend hours in. According to police records, Attila was stopped at his apartment at 11:15 a.m., taken to the district police station and questioned at a different location, the Teve Street police station at 3:15 p.m. when he was arraigned. There is no explanation as to why the four-hour wait was necessary during which nothing happened to him at the district police station, except for the circumstances and the uncertainty causing him anxiety. The investigation was not led by the district police in the first place but by the Budapest Police Force (BRFK), to where Attila was transferred in handcuffs by the officers.

Meanwhile, the celebrations of the Founding of the Hungarian State were underway with church and state leaders getting ready for the mass and procession in front of the Basilica, which lasted from 5 p.m. to 7 p.m. The interrogation of the handcuffed Attila ended at 6 p.m. after which he was still kept in custody. The police told his partner to pick him up at 7.

I first addressed my questions about the circumstances of the arrest to the BRFK. Did the police respond to the archdiocese’s request when they “prevented” the individual in question from “disrupting” a church event on August 20? Has Budapest Police Chief Tamás Terdik taken any action in this matter? Is it often the case that church leaders ask the police to take action against a private individual? Is there a legal procedure for the police to keep someone away from a public event if there is no warrant against them?

“The Budapest Police Headquarters has concluded its investigation in the case you refer to and has sent the documents to the competent prosecutor's office, so please contact the prosecutor's office for more information,” – was the police's response, and they did not provide any further information on the case despite additional requests.

So I turned to the Prosecutor's Office and asked them, among other things, why they did not subpoena Attila for questioning. Why was it necessary to arrest him? What reasons justified the decision to arrest him at 5.39 a.m. on August 20, 2019? What reasons justified the issuance and immediate execution of the warrant outside working hours? On what legislative grounds were coercive measures (handcuffs, restraints) used? Why was it necessary to bring Attila first to the district police station and then to the Police Headquarters? What reasons justified the intervention of 5 police officers against Attila in a public place? Why was his interrogation not undertaken on the next working day, especially considering the fact that the investigation had been opened on June 5, 2019?

"Some of the questions you have asked do not fall within the competence of the Prosecutor's Office, while others may be examined in the course of the ongoing judicial proceedings in which the court decides on the charges and the evidence supporting them,” – replied the Prosecutor's Office.

I then asked the Ombudsman some of the same questions in more general terms. For example, in what cases does it happen and what justifies a person accused of a misdemeanor, with no criminal record, not on the run, and not a flight risk, not being called in for a first suspect interrogation but being arrested?

“The questions submitted do not imply issues of concern to the Office of the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights,” – replied the Office of the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights. When I explained what it was about and that I had no idea who else to turn to for information, the press office asked for a little patience – but in the end, after the police and the Prosecutor's Office, the Ombudsman also failed to respond in substance, as did the archdiocese concerned and its leaders, Erdő, Snell and Süllei.

August 21.

One of the first things Attila did after his interrogation, which is also in the case file, was to inform the police of one of the most significant circumstances for him: he had a flight ticket for August 23. He was afraid that he would not be able to go on his last family trip with his terminally ill mother, and that he would not be able to leave the country because of the charges. Half an hour after he was released from the Teve Street police station, Attila wrote to me: “I was detained... I was arrested. They led me away in handcuffs. I was incarcerated because I was reported for harassment by Süllei and the others. I don't want you to write about it. As far as I'm concerned, I quit.”

But it was not over yet. The next morning, on the 21st, a major article appeared on the independent conservative portal Válasz Online, which the author claimed to have started working on at the beginning of the summer. When I asked him about it, András Stumpf said that he did not recall receiving any requests from his sources that the article should appear only after August 20. The reason why this question occurred at all was that the events followed one another in terrifyingly close succession: if the article had appeared only a little earlier, Attila would have been able to find out the rather important piece of information that Süllei had reported him for harassment. It was lucky for the investigators who wanted to apprehend Attila spontaneously. Had he known about the complaint, the surprise would have been ruined.

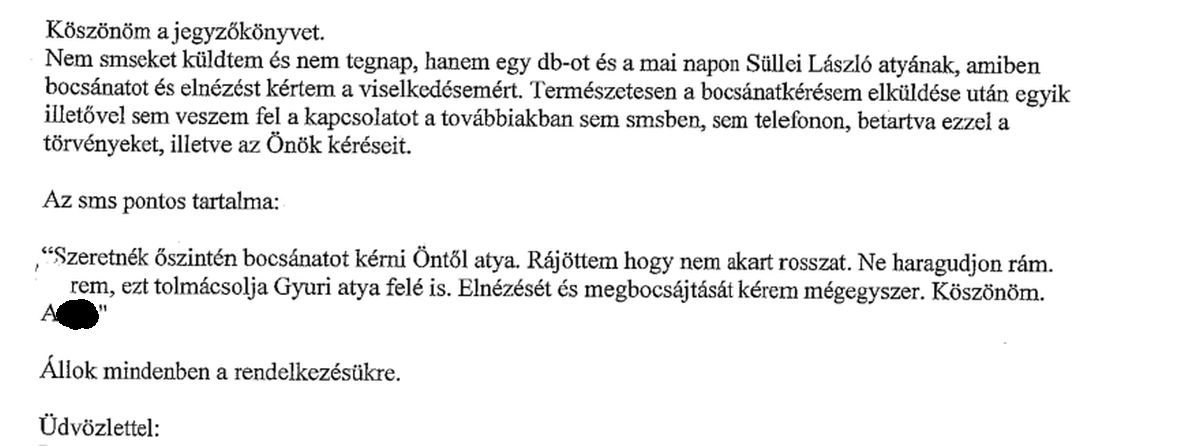

The article reconstructed the events “on the basis of investigation records and information from church officials”, and repeatedly underlined that it had “informally” obtained internal church documents that had previously been withheld from the victims themselves. In a follow-up article, Stumpf reported that Attila called him half an hour after the article was published on the 21st: “It may sound strange, but I want to thank you for this article. Now that I've read it, I see I may have overreacted. I didn't mean any harm and now I see that the Church didn't either. I'll stop now.”

Following the interrogation on the 20th and the article in Válasz Online on the 21st, Attila quickly tied up all the loose ends. Six months later he would conclude by telling me: “they have managed to break me”.

While the changes he wanted to achieve still seemed largely unattainable, Attila retreated: he publicly declared that he had “overreacted” and that “the Church meant no harm”. In a text message, he apologized to Süllei and Snell, the men who had reported him, and promised not to contact them again, expecting no further response.

The public part of the story ended with the third article on Válasz Online in September 2019. This was about the bishops’ apology, which was in no small part achieved by Attila: “We pray for the peace of mind of the victims of such irreparable acts, for the healing of the wounds, and we ask for forgiveness on behalf of the perpetrators.”

“This is surely where this story ends,” – Válasz Online concludes – “and with a happy ending.”

In November 2019, it seemed that the investigation by the authorities was also coming to an end: the head of the Criminal Investigation Department of the Budapest Police Force (BRFK) closed the investigation against Attila “for lack of criminal offence”, which was launched in response to the private petitions of the two prelates of the Esztergom Archdiocese, Bishop György Snell and Vicar General László Süllei.

The question is how reassuring such a closure would have been for anyone when the victim of the priest is not brought to court but Attila is still afraid to tell the public what happened to him. His mental state is reflected in the fact that he did not even dare to file a complaint against the way he was arrested, even though he felt it was unlawful and his lawyer advised him to do so, too. Then, at the very last minute, the prosecution took notice.

After the police closed the case in November 2019, the Budapest 5th and 13th District Prosecutor’s Office did not order the case to be continued within the prescribed time limit. Two and a half months later, however, the chief district prosecutor reopened the case and, seeing that the one-month deadline had expired he turned to the judiciary. The judge shared the view that the “manner, number and chronological frequency of the contact attempts give rise to a reasonable suspicion of systematic and persistent offences” and that Attila's “intentions extended to arbitrarily interfering in the daily lives of the victims.”

The harassments of Attila

The complaints filed by the leaders of the Esztergom-Budapest Archdiocese meant that after years of sexual abuse by their priest, years of inquiries, rejections and belying, a police investigation and a handcuffed witness testimony, Attila was now facing a judicial trial, too. While dreading a prison sentence, Attila was not left alone to face a potentially years-long trial: the Helsinki Committee took on his representation.

In her motion, Borbála Ivány, a lawyer working for the rights organization, argues that “in this case Attila acted in the legitimate interests of the victims in a highly sensitive case concerning human dignity and sexual autonomy in which he himself was personally implicated for many years as a child. Attila was right to assume that the Hungarian Catholic Church also has a goal, interest and priority to protect child victims to the fullest extent possible and that its leaders will act effectively to achieve this. Attila has always believed that the Church has a duty and responsibility to investigate and address child sexual abuse.”

The motion summarizes the emails, text messages and calls that are in the investigation file for which the police requested the call log from the phone company and interviewed witnesses. In cases of harassment under Article 222 (1) of the Penal Code, victims are usually threatened, approached violently and insulted. Here, there was no such allegation; the petition mainly concerns missed calls and unanswered messages sent on official business.

Two of the personal contact attempts are mentioned in the case file, both at the parish near the St. Stephen's Basilica. The Prosecutor's Office writes, for example, that the accused appeared twice at the home of György Snell in May 2019 and “on the first occasion, at around 10 pm, he kicked the front door and, as no one would let him in, he left the premises. The next day, the accused appeared again at the above address to contact the victim György Snell, during which the accused Attila asked the victim György Snell to support him for the sexual abuse he had suffered as a child by a now-laicized priest and to help him to get Cardinal Dr. Péter Erdő to apologize to him, otherwise he would disrupt the masses and create a public scandal.” The lawyer's motion, on the other hand, says: “In his desperation and because of the hopelessness of the situation, Attila did kick the door once as he said in his statement. However, the act was certainly not likely to cause alarm to the people in the parish.”

Furthermore, according to the motion, “it was never said that if Peter Erdő did not apologize to him, he would create a public scandal”, but instead Attila said that "during the sermon he will ask Snell to tell the people involved that he feels guilty about the matter.”

According to the motion, Attila's attempts to contact the diocese were like calling a customer service line to no avail: it is a case of “mismanagement of an office, which could be compared to the numerous attempts of a citizen to call the public service provider because their attempts are unsuccessful. In the latter case, it would be obvious to everyone that it is not a case of harassment.”

In a grotesque interlude in the transcripts the police make two notes of the fact that they repeatedly called Snell and Süllei, but they never answered the phone.

“György Snell himself stated in his testimony that he was not worried about himself but about the sanctity of the holy masses and the peace of those attending. This confirms our claim that Attila did not interfere in György Snell's daily and private life at any time and had no intention to do so” – is a key sentence in the defense argument. The statutory provisions on the basis of which Attila is to be convicted are: “[someone] with the purpose of intimidating another or arbitrarily interfering in the private life or daily life of another, regularly or persistently harassing that person...”

Regardless of the moral judgment of the actions against Attila, or the message the Archdiocese of Esztergom is sending to the victims, it is also important to ask to what extent the complaining Catholic magistrates received special treatment, and how strict the authorities were with Attila. Fortunately, we were able to ask an expert who played a key role in the creation of the statutory provisions.

Meanwhile, in the real world

“This procedure is nothing like the one we are used to seeing", says Júlia Spronz, a lawyer who mainly works on defending victims of violence against women at the Patent Association’s legal aid service. Along with other women's organizations, Patent lobbied for the introduction of harassment in the Penal Code in 2007 (now Article 222 of the Penal Code), which, according to Spronz, required that prominent members of the then ruling parties receive letters containing white powder so that they could experience first-hand the lack of legal protection against harassment.

While the bishop’s complaint prompted an investigation the same day, most cases of harassment against women stop at the point where the police delay the launch of proceedings and then reject the complaint on a variety of grounds. If an investigation does begin, it is most often closed without even interviewing the alleged harasser. In the investigation against Attila, witnesses came to testify one after the other, phone records were subpoenaed from the service provider, but other investigative acts such as reading, printing and scanning articles from Index.hu and 444.hu were also undertaken. Finally, in Attila's case, the police found no criminal offence but the prosecution reopened the investigation nonetheless.

Spronz would like to see the authorities do such a thorough job in the case of the abuse of ordinary (female) people because “for these victims, it really does take a toll on their lives. While we wait for the police and months go by, they live in constant fear. Many are literally getting sick of the harassment, which in their case involves more than a phone call or two.”

Finally, I ask about the arrest on August 20. Patent’s legal aid service has handled hundreds of harassment cases over the last thirteen years; how often has an alleged harasser been picked up by the police from his home? – I ask, and Spronz says without hesitation, “We have never had a case in our practice where they have gone to the scene. Never.”

Acceptance or fight

Attila was stopped by police officers on the street on the “national holiday and during the Procession of the Holy Right, which is an important event for him, and then he was arrested and taken to the 17th district police station in handcuffs and a harness, after which he was interrogated by two detectives at the Budapest Police Headquarters in Teve Street. At the end of his testimony, Attila had been subject to an unnecessary and disproportionate deprivation of liberty for nearly 7 hours on suspicion of a minor offence,” his defender said in her motion of March 2020, which also noted that “the investigating authority unfortunately did not interview any witnesses who were related to Attila and who might have knowledge, at least indirectly, of the events from his point of view.”

In April, however, the Prosecutor's Office closed the case: “Taking into account the minor material gravity of the offence, the circumstances of the offence, the suspect's criminal record and favorable personal circumstances, the motive for the offence, and the fact that the suspect stopped his harassing behavior during the investigation and apologized to the victims, the imposition of even the lightest sentence provided for by law or the application of any other measures against the suspect seems unnecessary, a reprimand by the authority expressing its disapproval is sufficient to deter the suspect from committing future offences.” This is the mildest possible measure and the law does not even call it a penalty. The decision does, however, stipulate that the suspect's act is capable of constituting a misdemeanor of harassment in 2 counts, in breach of Article 222(1) of the Penal Code.

At this point it became a matter of principle whether Attila would admit his guilt. If he accepts the reprimand then he is a free man. His years of torture are over and he doesn't have to look back. From then on, however, the Church could always claim that the best-known Hungarian victim, who was practically the only one to publicly report on the sexual abuse of priests, had been reprimanded for harassing the reverend priests. If he accepts the prosecutor's position that he has committed a crime, he will have lot less leverage to demand that the Church admit his harassment, that he be given the records of his case, that he be allowed to meet with Péter Erdő, and that the Hungarian Church in general be more supportive of those whose lives have been ruined by a priest. If, on the other hand, he refuses to be reprimanded and chooses to fight, he may face a more severe punishment.

I spoke to Attila several times while he was contemplating this last spring. He said he was afraid of prison. He knew, of course, his lawyer told him, that serving time in such a case was not a realistic option in the Hungarian legal system, but then neither was what happened to him on August 20. Finally, after a long discussion, and in consultation with the Helsinki Committee, Attila filed a complaint rejecting the prosecution's “offer”.

Declaring his innocence

“We are therefore of the firm opinion that Attila did not commit a crime,” reads the defense’s statement, which says that “the disapproval and reprimand of the authority is unnecessary and unlawful as Attila’s actions were lawful”, with the aim of better addressing child sexual abuse on a systemic level. “We therefore believe that the prosecution, which is called upon to act against the perpetrators of these crimes, should express its support for Attila, not its disapproval. We therefore commit to a public trial in which Attila will disclose the background and details of his actions and a court will declare his innocence.”

As expected, the prosecution brought charges against Attila.

On September 15, 2020, the Pest Central District Court – without a trial – passed the following sentence: the accused is placed on probation for a period of 1 year and 3 months for 2 counts of harassment [Section 222 (1) of the Penal Code]. This is a measure which is one more severe than a reprimand but it is still not legally a punishment and will not be entered on the criminal record.

However, if Attila had left it at that, a judge would have declared that “the accused, through his personal appearances, telephone calls, text and e-mail messages, sought to establish regular contact with the victims György Snell and László Süllei against their will, and harassed them by inconveniencing them and threatening them on several occasions, thereby arbitrarily interfering in their daily lives and disrupting their work.”

Attila and his defender were not appeased by this, so the trial could begin with a preparatory hearing on February 4, 2021 where the accused would be the victim of a priest and the victims would be the leaders of the Esztergom Archdiocese, Vicar General Süllei and Auxiliary Bishop Snell.

Péter Erdő expresses his thanks

The Cardinal has thus far not spoken. It is not only in this case that he has remained silent. As far as I know, Péter Erdő has never spoken publicly about child molestation cases. Which, if you think about it for a second, is incomprehensible. The universal Church has been struggling with child-molesting priests for two thousand years, it has been one of the most important issues for the last two decades, and some church historians say that not since the Reformation has this religion faced such a challenge. Naturally, Popes Benedict and Francis have often discussed it. They have met with victims and bishops all over the world have had to spend a lot of time setting up relevant regulations and reporting systems. But Hungary’s first prelate avoided the subject.

After looking through the court documents and talking to Attila, I tried to contact Süllei and Bishop Snell, but to no avail. And on January 7, 2021, I sent my questions to Péter Erdő, including these:

To your knowledge, has it ever happened in the history of the Catholic Church anywhere in the world that a bishop or even a cardinal – or in this case the diocese under his leadership – has filed a complaint against a victim who had been molested by one of his priests?

- What message do you think such a response sends to the victims, irrespective of the outcome of the secular judicial process?

- Has your diocese previously requested sanctions from the police against specific people?

- Were you aware that the police had taken Attila away and detained him at the very time of your mass on August 20? What do you think of this strange coincidence?

- In Attila's case, do you think it would be possible for the Catholic Church to establish that he was a victim of molestation by a priest? If not, why not?

- Would it be possible, in your opinion, for the Church or for you personally to apologize to Attila as countless prelates have done with victims abroad?

- Do you agree that speaking out for victims in public plays a positive role?

- Do you agree that Attila's action – whatever you may think of him – has contributed to the purification of the Church, to greater transparency, to the revelation of the truth?

I sat back in the comfort of the hopeless, only to receive an unexpected response less than a week later – albeit through a fellow journalist.

Válasz Online, the same news portal that published the archdiocese’s narrative the day after the police arrest, published an interview with Péter Erdő on January 13 on the occasion of a controversy surrounding the construction of a new church, but he also spoke at length about Attila’s case in particular. He has been the Primate of Hungary for almost twenty years, and child molestation has been an important issue for at least as long, during which time he has given hundreds of interviews and this was the first time this issue had come up? – I wondered. András Stumpf, the interviewer said that since he had been following Attila’s story for a year and a half he knew about the February trial and when he asked for the interview, he mentioned it as a potential subject to the Cardinal’s staff, citing its topicality.

This part of the interview had practically no repercussion, as without the back-story it was difficult to understand what the cardinal had to say, although in his reply there was one, in its own way historic statement: Péter Erdő thanked a victim for reporting the molestation.

He said of Attila: “By taking on the task of actually coming and making a responsible complaint to us, he started a process, which later spread to others and ultimately led to the resolution of the situation: the dismissal of the priest involved from the Church and from priesthood. So, in this respect we owe this man a debt of gratitude.”

In other words, not only did Attila succeed in getting the episcopate to apologize to the victims and the Cardinal to end his decades of stubborn silence, but he also succeeded in getting Erdő to say that victims who turn to the Church deserve thanks and that whistleblowing can be a solution.

Erdő’s answers also reveal a lot about Attila’s case, which he has also failed to address until now. I quote the interview:

“The diocese is not involved in any litigation with him (...) what is happening now is not a dispute between him and the diocese.

Didn’t you file the complaint against him?

Let’s not confuse a complaint with a private petition for harassment. A report was indeed filed by members of the diocese back in the summer of 2019 when the person was sending messages about planning to disrupt masses (...)

Is that why he was taken away in handcuffs that year just before the holy mass on August 20?

I don’t know if he was taken away, and if so, why. The fact is that the service took place in peace. The trial you mention is therefore a completely separate issue from this case. There is a lawsuit on the basis of a private petition – not with the diocese because a legal person could not even file a private petition.

But your colleague can. Wouldn’t you have thought it a better idea if the priest in question, exercising the Christian virtue of forgiveness, had withdrawn the motion?

No one asked me about this. Besides, it is not possible to withdraw a private motion. There is no legal way. On the other hand, I repeat, this is not a matter for the diocese. In any case, we have no grudge in our hearts against this man.”

Erdő thus tried to deflect the matter in various ways: his diocese is not in litigation with Attila; they have no dispute with each other; and it is not his business that his subordinates reported Attila; and he was not even asked about it.

It is true that Erdő did not go to the police in person but as Archbishop he is primarily responsible for his flock, the priests and the faithful of the diocese; the legal action was taken by his direct colleagues, one of the actions was specifically on behalf of the archdiocese he leads; and the witnesses were all his subordinates. One of the starting points of the whole procedure is that Erdő had to be “evacuated” from St. Stephen's Basilica when Attila wanted to talk to him – both the accusers and the witnesses were concerned about Erdő and the masses, which they wanted to protect from Attila with the help of the authorities.

There is another way

As there are always extreme opinions when it comes to child molestation, it is important to stress that the Church is not united on the issue and even in this country there are many different ways of handling these scandals. But the actions of particular institutions and even individuals are not black and white either – I will give some interrelated examples.

For Attila, personal relationships are important, as a believer it means a lot to him when a priest listens to his story, and he believes it is important for the magistrates to be accountable at a systemic level. And while Péter Erdő refused to hear of it, the Holy See’s ambassador received Attila in a private audience. But neither the nunciature, nor the archdiocese has done anything to inform the victim of the progress of the investigation. However, a leading Vatican expert and adviser to Pope Francis called this a “worrying” shortcoming of the regulations when I asked about Attila’s case in 2019. Hans Zollner added that, although it was not mandatory, bishops could decide on their own to apologize to a victim. However, it was not the Hungarian archdiocese but the Vatican headquarters that at one point in the proceedings said – in a way that was difficult for lay people to digest – that it was sufficient to “scold” the priest who by then had been accused of molesting other children besides Attila.

And speaking of Zollner, in 2017 he published a paper translated into Hungarian with these lines: “Finally, another component of the strangely Catholic mixture that enables abuse and prevents its exposure is an attitude that can simply be called a ‘fortress’ mentality. They want to settle everything ‘among themselves’ and out of the public eye because they fear for their own reputation, while forgetting about the suffering of the victims (who must be silenced) and the law of the media world, namely that: Sooner or later it will come to light. Take control of your actions, admit failure, apologize sincerely, and they will believe you.”

I tried to reach as many members of the clergy as possible about this case and the phenomenon but those directly involved were silent and others stonewalled me. I did, however, find a former and an active priest who have been following Attila’s story closely and were willing to talk about it.

One of the witnesses for the defense is a former monk who is still officially a priest but has left the order and now works as a university professor. They attended mass together with Attila and also travelled together to Pannonhalma. “As a pedagogical professional (...) who worked with disadvantaged youth, I also had a professional knowledge of what sexual abuse meant for a young person or child, how to deal with it and how to prevent it. What I saw was a professionally amateurish and, I must say, humanly inadequate approach by the representatives of the church”, reads his written testimony.

These “culminated in a kind of negative climax when he was arrested and handcuffed on August 20 to ‘prevent any harassment’. He, the victim. Again, this is retraumatizing and I would certainly have made an international scandal out of it. In this case, again, I saw Attila as more patient than I would have been in a similar situation, or dare I say, than one should be. There should be much more angry and vocal action in response to such indifference. The fact that he is now the accused, he is the suspect, I find professionally and humanly totally unacceptable.”

Zsolt Bakos, the parish governor is a childhood friend of Father Balázs, the priest who molested Attila; they grew up together and attended the same congregation. He says about him: he put his heart and soul into his work, he had a charismatic personality and was very popular among the faithful and the youth. Like many others, he didn’t believe the rumors about Father Balázs until 2016 when, after the Index.hu article, he was approached by several young people who had also been molested by Father Balázs. “Everyone told the same story. You can't make this stuff up.”

Zsolt Bakos met Attila and his brother at the residence of Father Balázs in 2000, when György Snell, later auxiliary bishop, was the parish priest there. Now he told 444.hu: he sees the official shortcomings that came to light during the clerical investigation. “The procedure was characterized more by patronizing, control and intimidation. In a case like this, this is not acceptable. I am convinced that there was no intentional malice: on the one hand, they were protecting Father Balázs and did not want to believe the allegations about him at first, which complicated the procedure; on the other hand, they treated Attila as someone who was against the Church and the clergy. But Attila has repeatedly stated that he had nothing against the Church. On the contrary.”

According to the priest, it is also “unworthy” that the magistrates of the diocese filed a complaint against Attila: “after all, he was proven right, everything was proven through various humiliating trials, he really fought for it as the recently interviewed Cardinal also alluded to. But that was the end of the story, no serious compensation or apology was made, moreover, he was later charged with harassment...”

I also talked to the priest of the Archdiocese of Esztergom about the fact that there are also good examples within the Hungarian Church, for example in monastic orders. At this point, Father Zsolt, who had been calm until then, almost burst out, “I can't believe that we couldn't have brought this to a normal conclusion, to tell them what had happened, to sit down with the parents and the children, to ask them how we could help, to apologize... Both the victim and the perpetrator have been, so to speak, ‘dealt with’... and that's the wrong attitude.”

Without an apology, you can't

So far, we have been dealing with the Catholic institutional system, but the treatment of the issue cannot be separated from the social context, nor can it be pretended that such things only happen in the Church.

According to Viola Szlankó, psychologist and head of children's rights at UNICEF Hungary, many institutions in Hungary still prefer to treat past child abuse cases as a legal issue, thus deflecting responsibility, especially if the case is already time-barred by law. It is important that institutions dealing with children have a child protection protocol in place, which can help where the law is powerless and which can even address past cases.

In this respect, churches, schools, sports clubs or theatres, which are more frequently mentioned in the media, have an important role to play because in many cases their examples show that there exist internal institutional tools, whether investigations or sanctions or victim support programs, which, beyond the law, provide extra protection in a community.

A general apology may be reassuring but for many it is not enough – says Szlankó. In her experience, one of the most important aspects is for the victim to receive clear feedback from the institution’s leadership that they acknowledge what happened, take responsibility for it and have compassion for the victim. A common practice is the so-called restorative circle where the parties involved – victim, perpetrator, heads of the institution, etc. – sit down together to discuss what happened, how the parties feel, what the lessons learned are at an institutional level. And there is also a practice where, under certain conditions the organization pays damages to the victim.

“But reassurance or reconciliation cannot happen without a genuine human gesture of apology in most cases.” If this is denied and if the institution even files a complaint against the victim later, this obviously causes further serious harm, says the psychologist who would certainly not want to do justice between the parties without full knowledge of the details of the specific case but stresses that if an institution has the appropriate child protection policy in place, both the leadership and the staff have the tools to handle this type of cases effectively, not to mention prevent them.

The monastery

A few days after the arrest on August 20. 2019, Attila went on holiday with his family to Greece. He knew it would be his mother’s last big trip but he couldn’t shake the police case off his mind. “I could feel the constant tension out there as well and only calmed down a bit when we reached the island. And considering how shitty I felt before, I had my strongest God experience there,” – he said when we sat down to talk in the autumn of 2020.

“I decided to climb alone to a mountain monastery. I almost died by the end of the 3-4-hour hike. I was greeted by a lone priest who was visibly delighted to see a human being and gave me a long tour of the ancient monastery. We prayed and then he gestured for me to enter behind the iconostasis. There I saw a stunning mural of the Last Supper, hundreds of years old. It was very moving. I prayed there not only for my mother but also for the leaders of the Hungarian Church, because I am as imperfect a human being as they are, yet I wanted this to come to a rest and for them to apologize.”

The next day, the bishops issued a statement apologizing to all the victims on behalf of the perpetrators. Whatever happened to Attila before and after, he could not dismiss this as a sign.

Post scriptum

This is the end of the article published in two parts in Hungarian at the beginning of February 2021, the somewhat edited version of which you can read in English above.

Three weeks later, Attila Pető stood in front of the cameras with his full name and face, the first among the Hungarian victims of sexual abuse by priests to go public. Auxiliary Bishop György Snell died a few days later of COVID-19 infection. Vicar General László Süllei apologized during an open trial for mishandling Attila’s case and asked the court not to convict him. However, the court did reprimand him at first and second instance.

Shortly after the announcement of the final verdict in February 2023, András Hodász, one of the best known Hungarian priests and the most popular figure of the Esztergom Archdiocese, wrote about how he was molested by a priest as a child and announced that he would resign from clerical service. In his farewell message he asked the Church and the Hungarian society as a whole to try to understand what is going on in the soul of a victim. Our greatest failure is that we have abandoned them, Hodász wrote, concluding, “Let us learn once and for all: if the door is open, there is nothing to kick.”

Translated by Anna Klaniczay

A katolikus egyházat kétezer éve kísértik a gyerekmolesztáló papok, és nem tud szabadulni tőlük

A reformáció kora óta nem volt ilyen válságban a katolikus egyház. Ferenc pápa történelmi találkozóra hívta a világ püspökeit, de a kiskorúak szexuális zaklatásának csak az áldozatok fellépése szabhat gátat.

„Mert féltik saját jó hírüket, miközben elfelejtik az áldozatok szenvedését”

Az esztergomi érsekség egyik plébánosa névvel is vállalja: „nem méltó” feljelenteni azt, akit saját papjuk molesztált. Erdő Péter a távolból mond köszönetet az áldozatnak, de beszélni már nem hajlandó vele. Holnap kezdődik a tárgyalás.

Gyerekmolesztáló papok Magyarországon: az első lépések

A magyar püspöki kar vezetője szerint itthon azért nincsenek kiskorúak elleni szexuális visszaélések, mert nálunk érték a gyermek. Az összegyűjtött esetek és az egyházi elöljáróktól kapott új adatok más képet mutatnak.

Három éve eltiltották a papot, aki molesztálta, de az egyház azóta sem kért bocsánatot

Áldozatként küzd az egyházi bürokráciával 16 éve, és nem látja a változás jeleit. Az elmúlt hetekben már a bazilikában szórólapozott, és egy püspökkel folytatott beszélgetését is felvette.

A molesztált férfin keresztül üzenget egymásnak a püspök és az érsekség

Miután közzétettük a beszélgetésük hangfelvételét, a Főegyházmegyei Hivatal levélben ígérte meg az áldozatnak, hogy Snell György lelkisegélyt nyújt neki. A püspök viszont közölte vele, hogy dehogy.

Ferenc pápa tanácsadója Budapesten: a gyerekmolesztálás mindenhol jelen van

Direkt módon sem Hans Zollner, sem a pannonhalmi főapát nem akart vitatkozni a püspöki kar vezetőjével, aki szerint a magyar papok kivételek. De mintha másik világból jöttek volna.

Vezetőszáron vitték el egy pap áldozatát, az ünnepi mise végéig nem engedték ki

Erdő Péterék megkérték a rendőrfőkapitányt: „akadályozza meg”, hogy a molesztált férfi „megzavarjon” szentmiséket. Úgy alakult, hogy az illető az augusztus 20-ai ceremónia egészét bezárva töltötte.